The Sandhills calving system can help producers reduce scours during calving season.

Eight client ranches are trying the method, which is used south of the border but isn’t too common in Canada, said Dr. Tommy Ware of Veterinary Agri-Health Services.

So far, it’s been a success.

Read Also

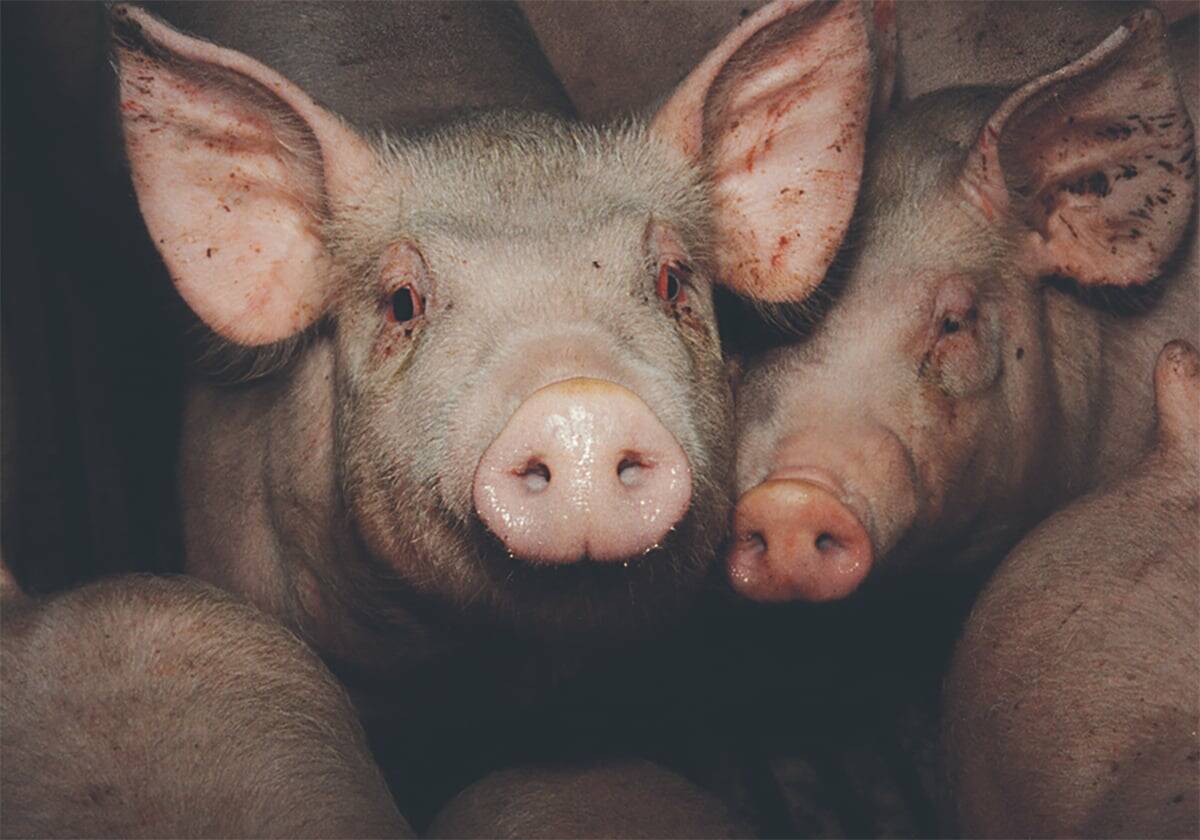

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

After years of research, a University of Saskatchewan research team has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and how to control it.

“Sandhills is our way of managing scours risk. Instead of trying to treat your way out of stuff, try to take a step back and look at it more from a management standpoint,” said Ware. “A lot of ranchers find it quite discouraging when they have to treat scours all calving season long.”

The method was created more than a decade ago in the Sandhills area of Nebraska when scours was a major issue in the region. It’s based on a simple premise: don’t allow calving in a particular pasture to go past two weeks.

“Our aim is to break those calves up into age groups,” said Ware. “The key is to make sure that when you calve in a pasture, you leave all the pairs behind, take all the pregnant cows and move them forward.

“With each move forward, every two weeks, you’re essentially starting calving in a new pasture.”

The system minimizes the risk that younger calves, which are more susceptible to scours and more likely to die from them, will be exposed to what older calves could pass on.

Ware learned the system at veterinary school at Mississippi State, where its creator was his mentor and teacher.

The Sandhills system is flexible and can be used by producers who don’t practice rotational grazing or spring calving, he noted.

“I’ve got one client up north. He took a quarter and broke that up into eight different paddocks. He still calves early in the winter and is still using a calving barn. Everything still comes through the barn, but once they leave the barn, they go into one of those individual paddocks.”

He firmly adheres to the two-week goal.

“If the first (paddock) fills up pretty quickly, he goes to capacity, and then he moves to the next one,” said Ware. “If he gets to the point where he isn’t reaching capacity, he just shuts the gate at two weeks.”

This method has been renamed “the Foothills calving system” by Ware’s fellow veterinarian, Dr. Elizabeth Homerosky, who discussed it at last year’s Canadian Beef Industry Conference. The Foothills calving system can be used by early calvers who need to use a barn in winter to protect calves from frigid temperatures.

“That’s where a barn is necessary and that’s where our modified Foothills comes into play,” said Ware.

Nanton rancher John Smith tested the Sandhills system last year.

“I liked it and I’m planning on doing it again,” said Smith, who runs a herd of about 500 cows with wife Laura Laing. “It’s just a matter of figuring out what works best, and some of the tactical things, like moving cattle around.”

Smith said he saw a difference in the number of sick calves.

His planned calving date is April 1, but he usually ends up starting on March 20 with his Angus.

“I started in one field,” he said. “Typically, before, with my mom and dad, everything was set up for winter calving and we always used to pair out. I guess that was the one savings that we saved a lot of time not pairing out. It’s way faster to move the heavies than the pairs.”

Smith found a field that was close and kept his calving there for 10 days while the weather was good. With bad weather in the forecast, he moved the rest of the group to the calving field. Another two weeks saw a move to the next field.

“On the third move, it was pretty minor,” he said. “There were not that many cattle left to move. We had our facilities for the bad weather. I kind of plan on doing that again.”

Smith has access to free-standing panels and windbreaks, and has thought of building a 12-foot by 36-foot barn on skids to pull from field to field, with a maternity pen in it.

The Sandhills system does work better in bigger herds, said Ware.

“Because of the infrastructure costs and management in smaller herds, it’s a bit more intensive to do it that way,” he said. “In a bigger herd, you can make bigger cow moves. In a smaller herd, the infrastructure cost is the limiting factor. That’s not to say you can’t do it and it can’t work.”

The system is gaining fans.

“We have probably eight or so clients that are doing this,” Ware said. “I don’t know a single one who has gone back to the way they were doing it before.”

And they’re reporting a reduced incidence of scours and lower mortality from scours.

“If you have an outbreak, you’re sequestering it to one small group,” said Ware. “You’re not exposing your entire herd to this scours risk. You’re kind of limited to that one small paddock of cows.”

The biggest challenge for the method in Canada is adopting it for winter calvers, he said.

It works well for spring calvers who start in April or late March, said Ware.