El Niño is coming but don’t worry. It doesn’t mean this summer will be a blast furnace, say experts.

The weather phenomenon caused by a warming of ocean waters brings hotter weather, and many climate experts predict its return will result in all-time global heat records.

But there are a few things working against El Niño having a major impact on summer, said Dave Phillips, Environment and Climate Change Canada’s senior and best-known climatologist.

Read Also

How Earth evens out the energy input

Earth has surpluses of radiation in its equatorial regions, and deficits toward its poles. Our weather is a matter of Earth trying to even out the imbalance, Daniel Bezte writes.

First of all, no one knows how strong it will be, he said.

“It’s just beginning. We don’t know its true personality and character, whether it’s going to be a big one or a little guy — any of those things can happen. But I don’t think it’s going to matter in terms of what farmers need to worry about.”

Second, the phenomenon tends to affect winter much more than summer in our part of the world.

“In the summer it has a modest kind of influence (in Canada),” said Phillips. “It tends to be a warmer-than-normal summer, but precipitation is always a crapshoot. It tends to be a little drier in some areas, but not always.”

Current models suggest a 70 per cent chance El Niño will sustain itself through June, July and August and an 80 per cent chance it will do so from July to September.

“They’re not expecting this El Niño episode to really get itself going until fall,” said Terri Lang, an Environment Canada meteorologist in Saskatoon. “We’re actually in a transition period between La Niña and El Niño; we call it La Nada — just neutral conditions.”

The concepts of El Niño (“little boy” in Spanish) and La Niña (“little girl”) have been around for hundreds of years, with the latter associated with colder-than-average temperatures. Over the past 72 years there have been 26 El Niños, 25 La Niñas and 21 neutral years, said Phillips.

The La Niña that’s just ending began in 2020 but didn’t bring noticeably cool weather on a global scale. All three years were among the planet’s hottest eight years ever. (In fact, the hottest eight years have occurred in the last eight years).

It’s a bit of an oddity, but La Niña’s have been more frequent in recent decades, said Phillips.

“You would think there’s kind of an inclination towards more El Niños in a warmer world with warmer water but that’s not the case. It shows you how complicated this is and that there are other factors at play.”

Still, the hottest-ever year on record globally was 2016, which was also a strong El Niño year.

However, each one is different and they can confound expectations, as did the El Niño in 2015-2016, which was the strongest in recent decades.

“We ranked the warmest to the coldest summers on the Prairies and the summer (of 2016) came out the 23rd warmest of 75 summers (and) precipitation-wise it was the eighth wettest,” said Phillips.

“That translates to pretty good. I don’t know what productivity was like in 2016, but certainly the temperatures were decent.”

However, Alberta was warmer than the Prairie average, and that summer was the tenth warmest in 75 years.

The real wild card this summer will be precipitation.

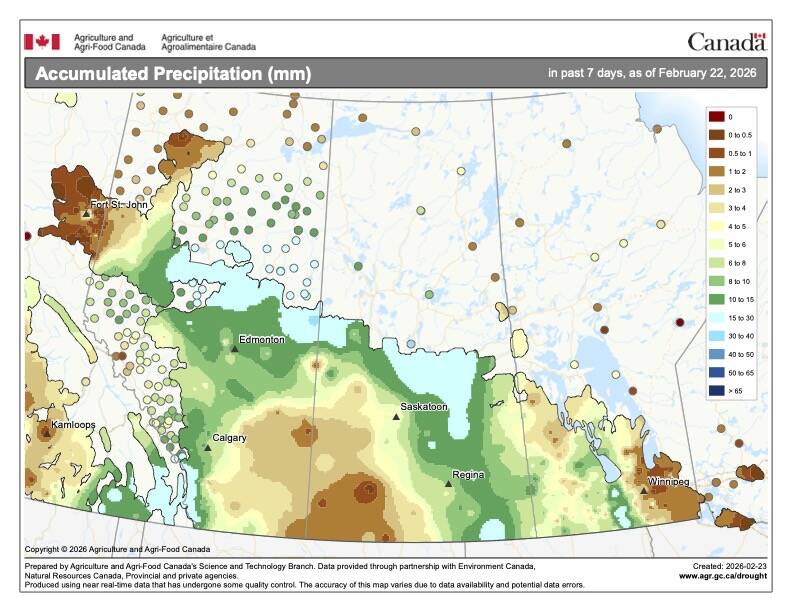

“Going into the growing season, there are some concerns on the Prairies, particularly in Manitoba and eastern Alberta showing areas that had less than 40 per cent of precipitation over the last 90 to 100 days,” Phillips said April 28. “Even with recent rains, some of the grain-growing areas are still fairly dry.”

At the time of the interview, the forecast was for a wetter-than-normal May, but as always, it’s what happens in June that really matters.

“You don’t lose your crop in April or March,” noted Phillips.