Much of Alberta will need as much as three times the usual amount of snow this winter to get out of drought conditions before spring, says an AgCanada agro-climate specialist.

“We’re looking at 250 per cent to 300 per cent of normal snow accumulation or large snow accumulation added to early rainfall,” said Trevor Hadwen. “We need to both replenish the soil moisture, but also the water supplies that normally come from snowmelt in those drier regions.”

While some areas received some decent rains during the fall, big swaths of the province are bone dry.

“The most significant concerns for dryness are in the Medicine Hat and Brooks area, as well as Red Deer through to Edmonton and the northeastern corner of the agricultural zone of Alberta,” said Hadwen. “To put it in context, places like Red Deer had one of their driest falls on record.”

The area just east of Edmonton is also very dry, as well as areas around Vegreville, Bonnyville and Lloydminster.

“It’s all adding to the drought we had in the summer and certainly not improving the conditions moving into next year,” he said.

Some areas — notably the Peace and around Calgary and Lethbridge — have seen conditions improve over the fall but the overall picture is not good.

“Despite recent moisture, only a few areas have had soil moisture reserves rebound to a near-normal condition for this time of year,” the provincial Ag Department said in its most recent (Nov. 16) soil moisture update.

The report also tried to strike an optimistic note, saying “there is ample time to accumulate reasonable snowpacks and receive timely rains in the early spring.”

“The meteorological record is replete with abrupt shifts between wet and dry spells,” the report states. “Thus utilizing recent weather trends to predict future weather trends is simply not advisable.”

Read Also

AgSphere cultivates new era for agri-food innovation

A new Calgary-based hub seeks to join universities, investors, multinationals and start ups to spur cutting-edge advances in farm-to-fork sector.

And while Hadwen is quick to say he doesn’t have a crystal ball either, he still said that producers would be wise to think about what they might be facing this spring.

“Even if we get normal snowpack, we’re going to still be dealing with the impacts of drought from this past year,” he said. “Even if things start to recover in terms of moisture levels, our forages and pastures will still be under stress from the previous year.”

Waiting and hoping

By early December, Kim Owen had received a fair amount of snow on his operation near Wrentham, about 50 kilometres southeast of Taber.

But none of it stayed.

“Total accumulation would be 10 inches,” said Owen. “The wind blew it all away, and we’ve had wind constantly. Our soil moisture is totally depleted.”

A pair of photos that he posted on social media this summer showed the impact of drought in very stark terms.

Each photo showed his father Richard standing in the same spot in the same field. The first, taken in July 2020, showed him standing in waist-high barley — a 100-bushel-an-acre crop. In the second, taken 12 months later, sparse and spindly stalks aren’t much more than ankle high.

“We had a really good start, actually,” recalled Owen, who grows canola, wheat, durum, barley and lentils. “Then the heat hit and no rain, and the heads didn’t fill and there were aborted heads.”

Like so many farmers whose fields have dried right out, Owen will need either lots of snow (that both stays and doesn’t melt too fast come spring) or timely rains next year.

“Right now, we’re in dire need of moisture,” he said. “I sure hope for a better moisture situation but it’s not looking very promising. But it’s early.”

Dry weather agronomy

And while Mother Nature may yet come through, there are some things that farmers should be thinking about given the prospect of dry conditions in spring, said agronomist Kristina Polziehn.

Growers should look back at the herbicides used in 2021, as some compounds can leave residues that can affect crops the following year when moisture levels are low.

“Take a look at what your moisture content has been on those fields going into the 2022 growing season,” said the owner of Axiom Agronomy in Sturgeon County. “Have you been using a lot of residual Group 2s or residual Group 4s? Then you might want to look if there are any sensitive crops going on the fields.”

She also recommends using soil moisture probes or sensors to more accurately assess moisture levels. If soil has low moisture, yield potential will be reduced even if there’s lots of nitrogen available, she said.

“Some growers may be more inclined to push the amount of fertilizer that goes down with the seed row. You may be limited if the soil is really dry come springtime, so you might want to back off on those type of applications.”

Polziehn also recommends thinking about alternative management practices, such as seeding earlier.

“There’s been lots of discussion on early seeding of cereals,” she said. “Taking advantage of some of that early-season moisture that may be available there would also be key.”

Proper seeding depth is extra important in a dry year, especially for small-seeded crops.

“It’s never great to be chasing moisture. Stick to proper seeding depths, hoping at some point, it will rain and you get the moisture to get the crop off the ground.”

A dry season can also mean extra insect pressure.

“August was a nice warm window, so there is an increased risk of cutworms in some areas,” Polziehn said.

Flea beetles can also be more prevalent in drier conditions so it might be prudent to use additional seed protection on canola seeds.

Finally, choose crop varieties that can tolerate a wide range of conditions, not just dry ones, she said.

“Hopefully we get some decent snowmelt from this winter into spring so we can recharge our soil moisture,” she said.

‘Plan for drier conditions’

Hadwen is hoping too.

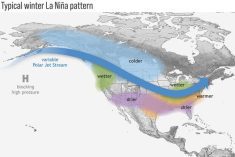

La Niña has returned and that typically means a winter that is colder, but also wetter, than normal.

“Last year, we were in a very mild La Niña and we ended up very dry, with not much snowfall and much warmer winter period,” said Hadwen. “This year, La Niña is a little bit stronger. We’re hoping it’s strong enough to provide a typical winter, which provides more-than-normal snowfall and colder-than-normal temperatures.”

The ideal would be lots of snow but normal, or even above-normal, temperatures because livestock producers have to feed their animals more when it’s frigid out.

“Feed is already hard to find and in poor supply right now,” he said.

And as expensive as it is, cattle producers may want to have extra feed on hand come spring, he added, noting that even if moisture conditions are good, it will still take awhile for pastures to recover.

“We don’t want to put cattle out to pasture as early,” said Hadwen. “We want to allow a bit of time to have those pastures to start growing before they are grazed.”

One hopeful sign is that precipitation patterns during the fall returned to “at least near normal across about two-thirds of the agricultural areas,” Alberta Agriculture said in its report.

But pragmatism needs to be mixed with hope, said Hadwen.

“Given the situation that we’re in now, I think it’s prudent for producers to plan for drier conditions and hope for wet.”