There were undoubtedly a lot of double takes when folks drove by Rob Stone’s farm last summer when he was out scouting.

That’s because the Saskatchewan producer was accompanied by a robot that wouldn’t look out of place on a lunar expedition, although it’s also been described as looking like a “glorified card table” on wheels.

Stone’s farm played host to the solar-powered Solix Ag robot, made by Brazilian company Solinftec, that uses high-res imaging, algorithms and artificial intelligence to identify weeds and measure crop health.

Read Also

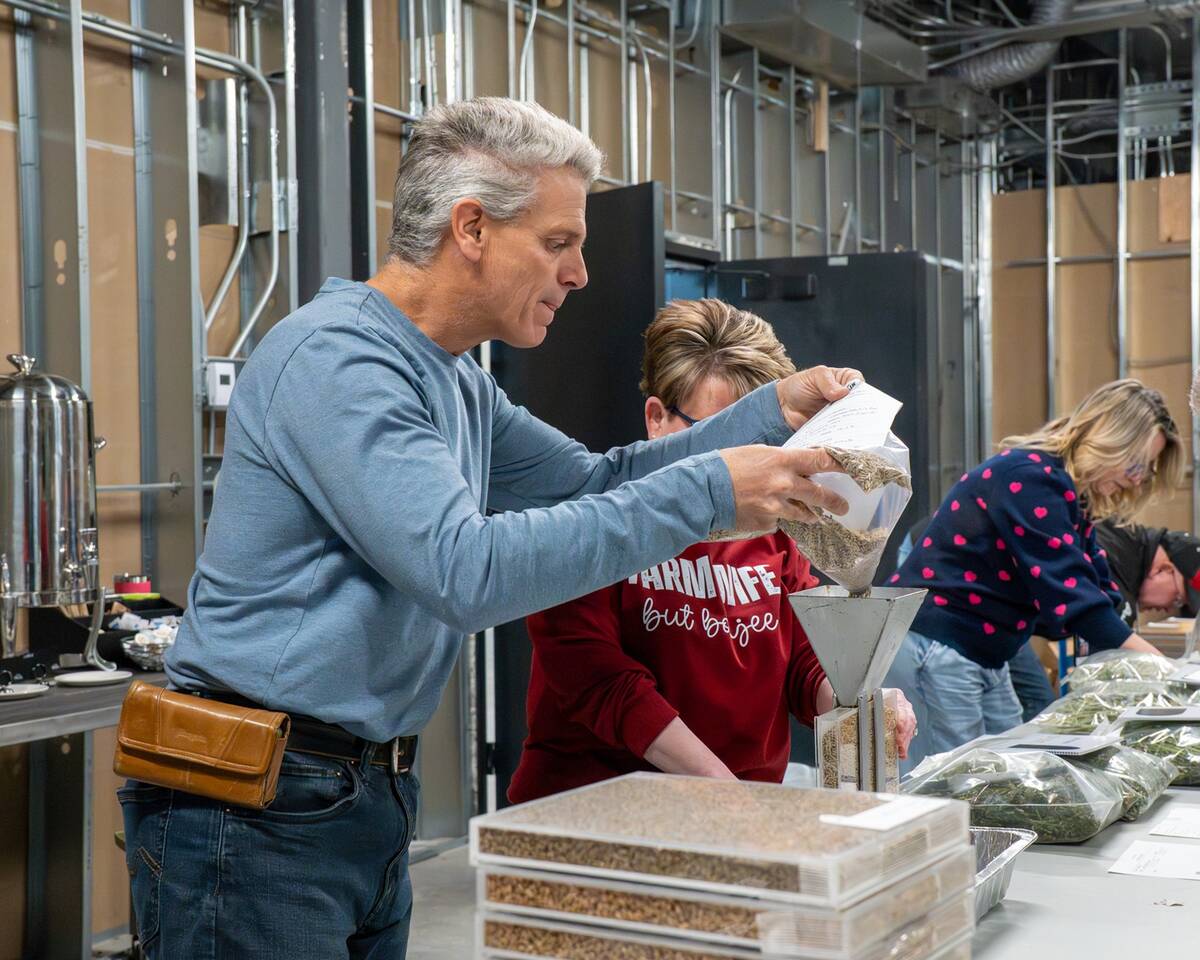

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

And while he doesn’t own the other-worldly device (it was trialled on his operation in conjunction with the University of Saskatchewan), Stone said he can see how this sort of advanced tech could be a fit on Prairie farms.

“Our motivation is efficiency and making the most of each acre. It’s expensive to farm,” he said. “And (also to) reduce environmental impact, either perceived or actual, I think there’s a bit of both right now.

“We do a great job on the farm, and I think we need to do a better job of recording and telling that story and proving it.”

[RELATED] Grainews: Brands target higher tech

On the other hand, Carl deConinck Smith’s sprayer might not get a second glance, but it too is a technological marvel.

“It is currently the only sprayer in the world that combines optical spot spray technology along with direct injection of chemical,” deConinck Smith said of his R4045 John Deere sprayer equipped with a direct chemical injection system manufactured by Raven Industries

“I could have up to 800 litres of glyphosate onboard that I inject separately for what is coming out of my tank right into my line, which helps efficiency and can change those rates on the fly at various parts of the field.”

From the cab, he can spray three different modes: full swath rate (which detects a weed and sprays only that weed), spray dual mode (which applies a background rate while spraying a higher rate in some spots) or full coverage.

Like Stone, deConinck Smith said it’s all about efficiency, in this case getting the optimum result with the least amount of chemical possible.

“This is green-on-brown technology,” he said. “Typical savings that we will find on our fall spray range from 90 to 30 per cent depending on how many weeds are present on the field at the time.”

Stone and deConinck Smith were two of three Saskatchewan farmers who spoke about adopting precision ag tools at the Canola Week conference last month.

[RELATED] The era of uniform application is ending as data drives change

The panelists not only highlighted how quickly tech is changing farming but also that getting the job done in the most efficient way is the unchanging foundation of growing crops.

“In terms of what precision agriculture means for us, it’s about efficiency and effective use of resources,” said Shayla Wourms. “No one wants to spend more time than they have to, and no one wants to spend more money than they have to.”

Wourms, husband Nick Wourms, and his family farm about 6,000 acres in northwest Saskatchewan, but in three separate locations spread over 100 kilometres.

But it’s not just about minimizing travel time. Field conditions vary wildly, too.

“We deal with a lot of diversity,” said Wourms. “We have black and some grey in terms of soil zones. We deal with a lot of variety in terms of topography — gentle rolling to extreme hills at a 23 per cent grade.

“And we have significant rocks. We’re talking major rocks below the surface that could ruin a lot of headers and drills.”

So mapping their fields is key, too.

“That’s how we use precision agriculture as well,” she said. “We’re able to provide that pinpoint on each part of those rocks, so that when it comes to harvest, we have those dead heads flagged. So we can weave around them, making sure we’re lifting the header up manually at those points and making sure we’re not going to crush a header or ruin the drill there.”

Stone’s farm near Davidson in central Saskatchewan has flat and rolling ground, too, and he uses yield mapping for variable rate. One of his key pieces of equipment is an 84-foot Väderstad Seed Hawk drill.

“The shanks lift up and go in the ground. It’s a great piece of technology,” said Stone. “It cuts our overlap down. This is our second or third drill with some sectional capabilities, but the most comprehensive, probably about eight per cent over solid seeding that we were doing before.”

Stone said he’s been playing with variable rate technology for fertilizer application and experimenting with different fertilizer products. He’s also been selecting three different rates with the applicator. And with the spray program, he’s been looking at different products to get the most precise rate.

“We like to track our field efficiency,” he said. “We employ the use of crop intelligence sensors. We really enjoy the information that comes in from them.

“What they don’t do is make it rain — but they certainly tell you how much resource you have underneath your feet. Decisions at times can be very easy.”

That sort of info is valuable both in the short term (such as knowing if there’s enough moisture to make top dressing worthwhile) and in tracking moisture use efficiency over long periods (for fine-tuning management practices).

Moisture is always on the mind of deConinck Smith, who farms with his wife, son, and parents in the brown soil zone of west-central Saskatchewan.

“Because of this, drought is always definitely on our minds,” he said. “We use this disadvantage and turn it into an advantage and use our long season available to us at seeding and harvest to use our equipment over very large acreages.”

The family usually seeds 9,000 acres and leaves 3,000 acres to chem fallow. Again, efficiency is the name of the game.

“We do a lot of acres with one drill,” said deConinck Smith. “We have a 68-foot drill and we’re seeding on our own farm, plus our neighbour’s 11,000 acres with that.”

But it’s not just the size of the equipment that matters. The operation targets precise application of nutrients and chemicals and employs spot spray technology.

“All of this tech helps with our profitability and our long-economic stability on our farm,” he said.

One piece of technology used on the farm is a Bourgault air drill with a “triple-shoot” system

and tanks with weigh scales.

“We have basically eliminated static calibrations, a time-consuming operation when you are switching from seed to seed and different fertilizers,” said deConinck Smith.

The tank scales also allow them to seed a variety of crops, eliminating clean-outs.

“At times, we’ll even seed two different crops in the same day,” he said.

But while the equipment and tech varied on all three farms, it’s the mindset that’s key.

It’s important to constantly do research and exercise critical thinking skills to make sure the farm is the best it can be, said Wourms.

That includes attention to everyday details, she said, pointing to her high-clearance sprayer with individual nozzle control.

“This is a big piece. It also means paying attention to the fact that nozzles have to be upgraded. You have to have the right nozzles. That’s kind of underplayed as well.”

And everything has to work as a unit, said Stone.

“We’re putting all our platforms together to document and track and better leverage all of the things that we’ve got going on.”

“All of this tech helps with our profitability and our long-term economic stability on our farm,” added deConinck Smith.