The cost of annual crop insurance is soaring by an average of more than 37 per cent this year — and many farmers could be facing an even higher bill.

“An average 1,500-acre Alberta farm growing a mixture of crops will see increased premium costs of approximately 54 per cent for annual insurance and hail endorsement,” Agriculture Financial Services Corporation said in a rate announcement last month.

A farm that size with a crop mix of 37 per cent canola, 28 per cent spring wheat, 22 per cent barley, and 13 per cent yellow peas would pay $52,027 in premiums — a hike of more than $18,000, according to AFSC’s example in the rate announcement.

Read Also

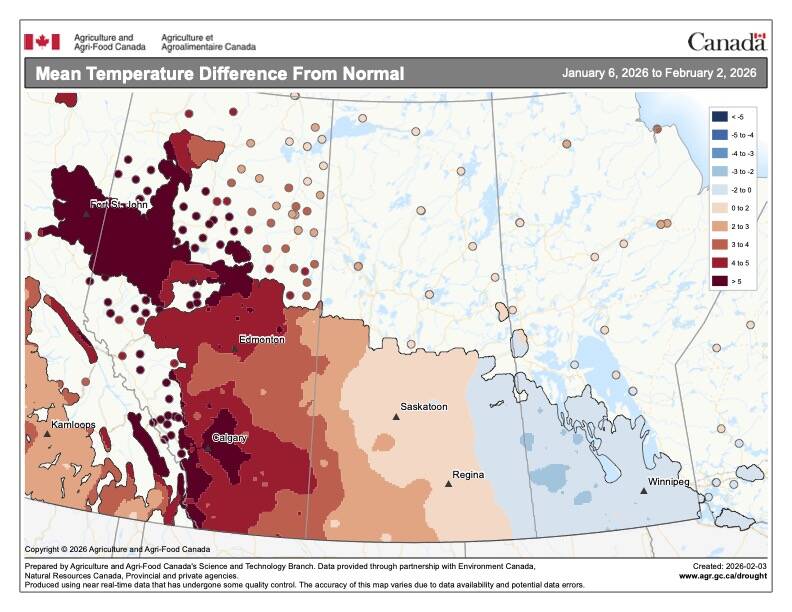

Prairie weather all starts with the sun

The sun’s radiation comes to us in many forms, some of which are harmful to organic life while others are completely harmless or even essential, Daniel Bezte writes.

But the biggest chunk of that increase isn’t because of last year’s drought — even though AFSC now expects to pay out a whopping $2.7 billion to cover insured crop losses, said Emmet Hanrahan, the insurer’s vice-president of product innovation.

“The biggest story is the commodity prices,” said Hanrahan. “We’ve seen commodity prices go up by close to 40 per cent year over year. That means basically the coverage increases, and you have to pay more premium to secure that coverage.”

In the case of the theoretical 1,500-acre farm with the above crop mix, coverage would be nearly $731,000 — versus $532,000 a year ago (or 37 per cent more).

“This is the coverage a producer can buy, which is driven directly by the pricing for commodities,” said Hanrahan. “That has increased substantially, so now a producer has to buy more premium to secure that coverage.”

But there are other factors that go into setting premiums, and the drought was a big one.

A year ago, AFSC said its insurance crop fund reserve had grown to the point where it expected it could cut premiums by 20 per cent for five years. But “record claim payments, the highest in its history, have resulted in a significant decrease in the fund reserve,” the crop insurer said in its rate announcement.

“The underlying premium rate has increased 10 per cent,” said Hanrahan. “It could have increased a lot more, but the methodology caps it at 10 per cent. That increase is driven by the decrease in the fund balance, and the 20 per cent premium discount not continuing.”

Individual circumstances matter, too.

Past claims can raise an individual farm’s premiums — something AFSC calls “adjustments” — while being claims free can lower them. That can increase or decrease premiums by as much as 38 per cent, based on a 15-year rolling average that is updated annually.

However, last year’s claims won’t affect this year’s premiums.

“There’s actually a lag in looking at the individual’s discount or surcharge that a producer might get put on their premium — 2021 doesn’t come into that calculation until we calculate 2023,” said Hanrahan.

“We limit the amount that a surcharge can increase in one year — this time to 15 per cent. The methodology promotes stability in the premium that the producer is paying. The premium surcharge or discount can be as much as 38 per cent, but it won’t change in any given year by more than 15 per cent.”

Producers can reduce their insurance cost by opting for a lower coverage level (which ranges from 50 to 80 per cent), but they should think carefully before doing that, he said.

“The investment that the farmer has to put in the ground before anything even grows is pretty substantial,” Hanrahan said. “When you think about those two things — the actual investment in the dirt and the potential value of that crop — you’re probably wanting to protect that and increase coverage, although it does cost more for premiums.”

The big increase in premiums also affects the province and Ottawa, which cover some of that cost.

“With the increased premium costs, the cost to the province and the cost to Canada have increased also.”

Meanwhile, the cheques to cover last year’s drought losses are still going out the door.

Inspectors are still finishing up the last of the post-harvest inspections, and were expected to be finished soon, Hanrahan said in a March 18 interview, adding about $2.4 billion has been paid out to date.

That’s more than triple the $780 million that AFSC paid out in 2019, which was likely the previous record amount.

“We expect it will be roughly around $2.7 billion when we’re done,” he said. “It is the highest payout we’ve had that I can remember anyway.”

That figure is also far higher than the $1.5-billion estimate given by AFSC chief executive officer Darryl Kay in mid-January.

But once again, soaring commodity prices played a big role, said Hanrahan.

“I should point out that a third of the $2.7 billion has been a variable price benefit, so that was paid out because of the commodity price increases in 2021,” he said. “That’s just a feature of the program. It’s when the spring insurance price moves over the year by more than 10 per cent that the variable price kicks in, and any losses are paid at that higher price.”

The bottom line is that the bottom line — in terms of the reserve fund — has changed dramatically in just one year.

“That crop insurance fund is producers’ money,’ said Hanrahan. “It is the money that they have paid in premiums and governments have paid in premiums, and it’s there to support the programs in years where we pay out more than we collect in premiums.

“At the beginning of 2021, it was sitting at $2.7 billion, and by the end of the year it will be below $1 billion for sure.”

Hanrahan estimated the reserve fund will likely end up in the range of $600 million to $700 million.

That kind of drop will take many years to recover from. In its last fiscal year, AFSC reported a surplus of $26 million; the year before that it had a deficit of $155 million; and the year before that its surplus was $150 million — a net surplus of less than $20 million over the three years.