Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will not only roil commodity markets in the short term, but could lead to some structural changes to agriculture both here and abroad.

- [READ MORE] Farming behind the lines in Ukraine

Livestock production, the rise of faux meats, phosphorus recycling and biofuels were some of the issues raised by ag economic experts on a panel convened by the Canadian Agricultural Policy Institute on March 9.

The Food and Agriculture Organization’s world food index is the highest since 1973, said Ted Bilyea, an agri-food consultant and former food company executive, noting wheat prices have soared by more than 50 per cent since the invasion.

“The end game is a lot of people are going to be hungrier,” Bilyea said. “And yes the prices will simply lower demand in not a very good way, but it will lower demand and that will be how we’ll get through this crisis. People will eat less.”

People will also eat less meat and more pulses, including “fake meat” made with plant protein, said Sebastien Pouliot, an agricultural economist with Farm Credit Canada.

“We’re already seeing people consume less meat than before… less beef, less pork and more chicken,” he said.

Canadian cattle producers were already suffering because of high grain prices following drought last year and the latest jump in feed grain prices will make Canadian beef production even less profitable, Pouliot said.

But Bilyea predicted high grain prices will see a shift, especially in Europe, on where meat is produced. Large livestock-producing countries like the Netherlands, Spain and Belgium were already net grain and protein importers. Where production isn’t subsidized or protected, livestock should move to grain and not the other way around, he said.

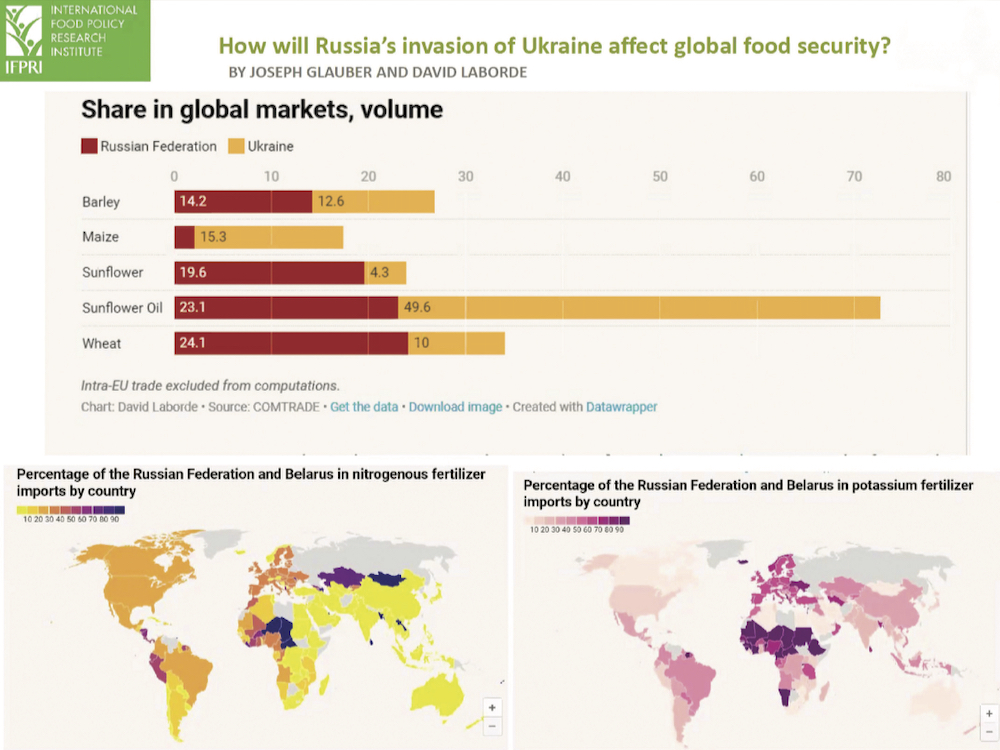

World fertilizer prices were up dramatically even before the war and are going higher, Pouliot said. Russia is a major fertilizer exporter, but sanctions will cut into sales. He expects this year Canadian urea will double in price from last year, while anhydrous ammonia and ammonium phosphate will jump 65 per cent.

World oil prices are up dramatically too, increasing farmers’ diesel bills.

“Pretty much all crops in Canada we expect them to be profitable… even though input prices are going up so much,” Pouliot said.

High grain prices will put pressure on governments and farmers to take marginal land out of conservation programs to produce more grain, said Shane Knutson, an ag equipment executive who has more than two decades of selling in Ukraine.

“What I do know in the short term people need to be fed and so we’re going to do whatever we have to globally to try to make sure that everyone gets fed whether that means, as Sebastien pointed out eating less meat in the short term, or doing whatever we need to do,” said Knutson, president of Polywest Ltd.

Bilyea agreed there’s an incentive to convert marginal land into grain production, but said it’s a mistake.

“We are going to destroy ourselves if we go that route,” he said. “You know taking cattle off grassland is an insane thing to be doing. We need the grasslands and we need the cattle on the grassland everywhere in the world.

“I think we have to come up with other ideas of how we are going… to be more productive, intensify productivity in a way that’s highly sustainable.”

The high, and increasing prices, of oilseeds has major implications for the plans of Canadian and American companies that are investing heavily in renewable diesel production.

“I do think this situation will affect how fast we go forward with all those things,” said Bilyea.

The food-versus-fuel debate has gone on for years, Pouliot said. So far government hasn’t announced any changes to renewable fuel mandates “and I don’t expect them to go away either,” he said.

Bilyea’s advice to the Canadian government now is “do no harm.”

“Some of the climate mitigation issues that were being put forward we could just delay those for a bit,” he said. “We don’t need to stop them. We delay them and work them into a more systematic change rather than do things overnight.”

Canada and other nations also need to be more resilient, he added. One way is to rely less on fertilizer imports. Canada is a net exporter of nitrogen and potash but relies on phosphate from the U.S.

“But we could be a leader essentially in recycling phosphate,” Bilyea said. “As you know every city in the world is a phosphate dump essentially and you could just recycle it through struvite back into farms.”

First though, legislative challenges are needed to allow struvite (a form of phosphorus that can be recovered from waste water) from humans to be used as a fertilizer, he said.

Ukraine and Russia grow mainly winter wheat, which is already in the ground, said Knutson, who has worked in both countries. What’s unknown regarding Ukraine is how well that wheat will be cared for and what will happen at harvest, he said.

There’s uncertainty about who will buy Russian wheat. Although clearly China will be one customer, how it will be shipped is unclear as Black Sea ports are closed due to the war.

Ukraine can ship grain by truck and train to European buyers, but Russia doesn’t have that option. It has ports in the far east but they lack the capacity to handle all the country’s grain exports, Knutson said.

– Allan Dawson is a reporter for the Manitoba Co-operator.