Although they only arrived in the Peace three years ago, the tiny bugs caused more than $1 million in damage and are showing up in fields across the province

Producers across Alberta are being urged to check their grade samples and be on the lookout for wheat midge.

The tiny bugs don’t usually cause huge yield losses, but some producers in the Peace Country and the southwest corner of Alberta were hammered in 2013 both on yield and grade losses. Damage in the Peace alone is estimated to have topped $1 million and in at least one case, cut yields by an estimated 50 per cent.

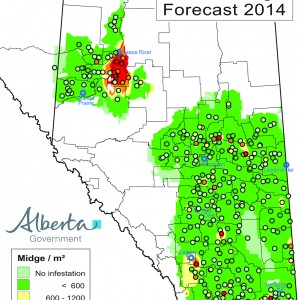

Those two areas are rated as hot spots for 2014, but farmers virtually everywhere need to be on guard, said Scott Meers, insect management specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development.

Read Also

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

After years of research, a University of Saskatchewan research team has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and how to control it.

“The risk in most of the province is fairly low, but there are individual fields almost throughout the entire province that are at risk,” said Meers.

Any area where wheat midge scouting found more than 600 bugs is classed as a moderately high to high-risk area. But being in the ‘green’ zone isn’t a guarantee of safety, he said.

“If you’re getting midge grading reports — even if it’s not affecting your grade, but being mentioned — you should be looking at management options,” said Meers.

“If it’s at the point where it’s affecting your grade, you should be considering midge-tolerant wheat. If it’s there but low, then I would do things like increasing seeding rate, seeding earlier, and putting together a proper scouting plan so you don’t get caught by a high level the next year.”

‘Caught’ is a good word to describe what happened in the Peace in 2013.

“To some degree, it was a bit of a surprise because when we did the fall soil sampling the previous year, we weren’t able to detect very high densities,” said Jennifer Otani, pest management biologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

Although common in Saskatchewan, Alberta has largely escaped the scourge of midge. It lays eggs in the wheat head, which results in the larvae feeding on wheat kernels.

Wheat midge — which are bright orange, about half the size of a mosquito, and have three pairs of legs — were only found in the Peace in the fall of 2011, said Otani.

“From that point on, we’ve seen the population increase,” she said. “The important thing to remember about wheat midge is that it is an introduced pest, so it is not native to the Canadian Prairies. This is not a cycle — it seems to be a new distribution on the Prairies, which is why it reached such huge densities in some of these fields.”

Worst-hit areas

Smoky River and Falher were worst hit. The outbreak prompted the Smoky Applied Research and Demonstration Association to put on three midge information seminars last month.

Weather played a major role as heavy rain delayed crop emergence in 2013, said Mike Dolinski, one of the speakers at the seminars.

“Because the crop was delayed, it was in synchrony with when the midge emerged and were flying and laying eggs,” said Dolinski, a former provincial entomologist with Alberta Agriculture and now a coach with Agri-trend.

One producer he knows lost 50 per cent of his wheat in one field, which was seeded May 23.

“That just demonstrates how important it is to get the crop in and up early to try to beat the midge emergence,” he said.

Midge causes the most severe damage when the bugs emerge at the early stage of wheat’s embryo development.

“Typically the recommendation is to spray right at the beginning of anthesis, in other words when the flowers come out or when the anthers are pushed out of the seed,” said Dolinski. “Most farmers don’t know how to tell when that is going to happen.”

The head is susceptible from the time the boot cracks until the anthers are ejected. Once the head emerges, producers should go out and open up a few florets on the primary spike, Dolinski said.

“Once you see a yellowing in the anther and the stigma spreading, within 24 hours it’s going to eject the pollen. Once the pollen is ejected and lands on the stigma, the next morning, it will eject the anthers and that’s when we see anthesis.”

The period between head emergence and pollination lasts for about five days, but is shorter when temperatures exceed 20 C.

If there are no midge flying, there’s not a problem, said Dolinski. If anthers have already emerged on primary spikes and there are no midge out and about, the wheat is safe.

“In other words, seeding early is really, really key,” he said.

Although yield losses are not generally severe, it doesn’t take much for a drop in grade.

“When the larva feeds on the kernels, they become shrunken and distorted,” said Daryl Beswitherick, program manager for quality assurance with the Canadian Grain Commission.

The commission tolerates up to two per cent of midge-damaged kernels in No. 1 CWRS wheat and eight per cent in No. 2.

In the Peace Country in 2013, 23 per cent of wheat samples received through the commission’s harvest sample program were downgraded. In the southwest corner, 30 per cent of samples were downgraded.

Alberta Agriculture’s 2014 wheat midge forecast indicates an increased risk in the eastern Peace region and a decreased risk in southern Alberta. Producers in high-risk areas should plant midge-resistant wheat varieties or could even consider planting a crop other than wheat, said Otani.

“This is the time that producers are making those decisions and we want to be aware that this is a new pest, the distribution has increased and the numbers in the field have really increased in that particular area,” said Otani.

Not planting wheat may not be a realistic option for most farmers, said Meers, but they have to be on guard.

“I’d be more inclined to say to be prepared to put management practices in place,” he said.