Those that have watched with some consternation the evolution of organic food marketing have been aware of a glaring discrepancy that advocates try to cover up. It has to do with a plain and simple question: how does one really know if organic food is really organic?

The reality with organic food is that on the whole consumers have no way of knowing for sure whether a product is really organic unless they grow it themselves. The only objective alternative to finding out if a product is really organic is to have it tested for prohibited substances such as pesticides and herbicides. That seems simple enough, but that approach has been fought tooth and nail by the organic food industry. That lobby has been very successful, being that present organic labels including government ones, are not based on strict, objective regulation, inspection and mandatory testing, but more on blind trust.

Read Also

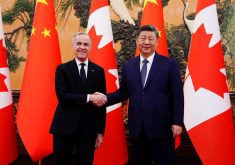

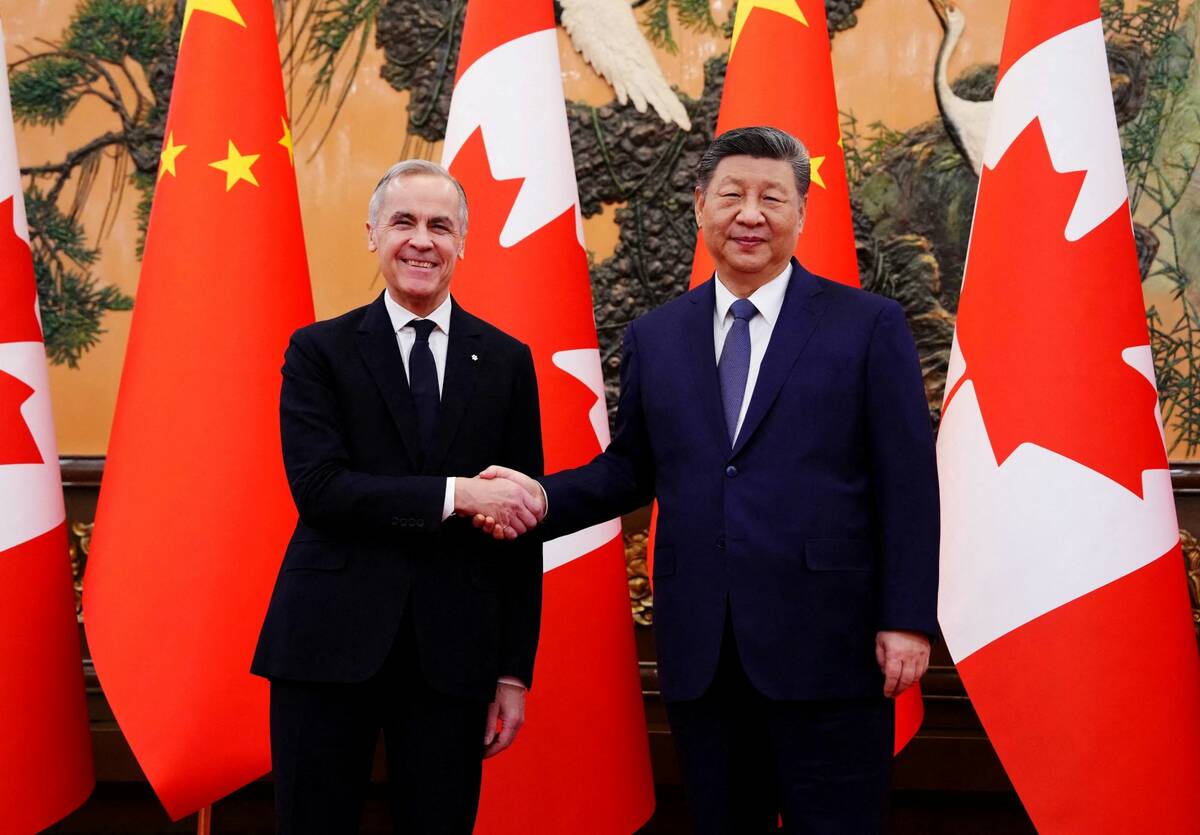

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

If that sounds suspicious or open to mischief, you are right, and a recent book by Mischa Popoff entitledIs it Organic?blows the lid off the bogus nature of organic food labelling and inspection. Mr. Popoff isn’t a mainstream food-industry spy – he is one of the organic food industry’s own. Popoff for five years was a professional organic farm inspector and an instructor. His job was to go out and determine whether an organic farm was actually following organic food production principles as outlined by the certifying body. If the farm or processor were officially certified for following the accepted principles and requirements, they could then stick an organic label on their products. That label is supposed to provide some assurance to the buyer that the product was indeed organic. That looked good on the surface, but there was more to the story.

Popoff says that the entire organic inspection/ certification process is nothing more than a questionable paper audit and a cursory look at the production practices and facilities. Because no sampling is done of the soil, plants, livestock or anything else, no testing is done to scientifically back up the certification. Testing is rather important because it would positively confirm whether the producer is actually following organic production principles or is perhaps fibbing. Rather than exercise the precautionary principle that green groups demand of everyone else, in the case of organic food the principle is “don’t worry, trust us.” Perhaps there is a perverse twist to that principle, that being the producer needs to take precautionary steps not to get caught.

That seems to have come to light in some of Popoff’s experiences. He notes that inspections were not to be random and unannounced which might catch a few cheaters. Instead those growers to be inspected were to be advised well ahead of time that an inspector was coming. Better forewarned than caught red-handed and not be certified. There is a vested interest in that, certifying agencies are money-making organizations that get paid to inspect and certify. One might expect that if too many producers are not certified it would see a reduction in the income of those agencies. Hence inspectors would feel the pressure to approve almost anyone, and inspectors questioning this system would soon find themselves in trouble with their employers, which seems to be what happened to Popoff.

The organic industry states that producers and processors are free to have their products tested for contaminants. But they do so at their own cost and peril. That’s because the odds are that testing in all likelihood will identify some prohibited chemicals which ended up in their products by accident or design. Either way that makes no difference to the organic industry lobby, as they want to maintain their “holier than thou” marketing image at all costs. That’s not unique to the organic industry, the mainstream food industry doesn’t like testing either. It’s deemed to be a costly nuisance that has to be tolerated.

The Popoff book does go beyond just the inspection issue. Clearly the author supports real organic food production. The book also contains a highly detailed history of organic practices going back 400 years. Although it causes one to ponder – wasn’t all food production organic before commercial fertilizers and chemicals came into use starting about 80 years ago? I quibble of course, the book is a very honest and enlightening perspective of the real story of the organic food industry and its powerful lobbying organizations.

Don’t hold your breath of ever seeing this book or its author in a CBC news report or documentary on organic inspection agencies. What Popoff is exposing is the credibility of the organic industry and its envirogroup allies, daring to challenge them on this issue appears to be politically incorrect to the mainstream media.

———

ThePopoffbookdoesgobeyond justtheinspectionissue.Clearly theauthorsupportsrealorganic foodproduction.