You can’t have cheap food and expensive oil. It just doesn’t work.

For hundreds of millions of people who earn only a dollar or two a day, increasing prices for staple foods like grains, pulses, rice and cooking oil is a big deal.

Canadians spend only about 11 per cent of their disposable income on food. If the price of a loaf of bread goes up by a nickel or a dime, there won’t be people rioting in the streets.

Read Also

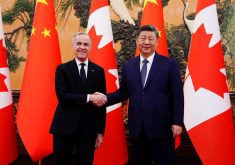

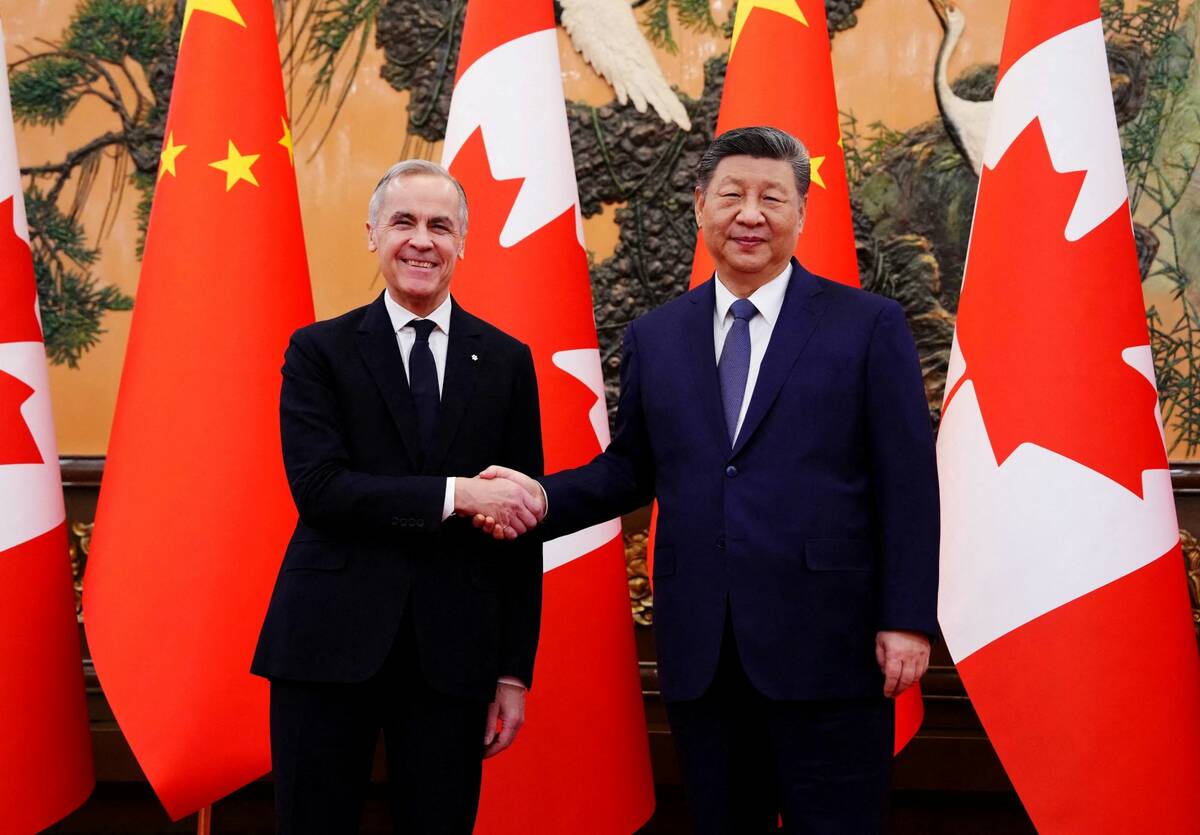

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

But food prices are causing riots in developing nations and have been linked to the uprisings in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya.

The latest farm income projections from Statistics Canada show record farm income levels for Saskatchewan. The realized net farm income, which takes into account depreciation costs, but not changes in farm inventory, shows $1.6 billion for 2009 and more than $1.7 billion for 2010.

By comparison, Alberta’s realized net farm income was only $264 million in 2009 and a dismal $64 million for 2010. The numbers for Manitoba are $553 million and $404 million.

However, if you take a look at the projection for realized net farm income in 2011, Saskatchewan is down to $592 million. The drop is caused by rising costs as well as declining government support. In fact, without the government support (programs like Crop Insurance and AgriStability) the realized net farm income projection would be zero.

While the $1.6 and $1.7 billion of the past couple of years is the best we’ve ever seen, it just compensates for previous lean years. (Adjusted for inflation, grain prices were much higher back in the early 70s. So was farm profitability.)

The ethanol industry is a prime target of those who worry about food prices. About 39 per cent of the U.S. corn crop goes to making ethanol. Cancelling the ethanol incentives is seen as a way to increase the food supply and drop prices.

There are faults with that logic. Less ethanol means even more upward pressure on oil prices, which in turn increases food costs. High fuel costs add significantly to the cost of food processing and transportation.

Besides that, if you cut ethanol production and grain prices drop, grain production will also decline. As production becomes unprofitable, there’s no incentive to spend money on new varieties and extra fertilizer.

So while it might be a short-term fix, cutting American ethanol production wouldn’t likely have a long-term dampening effect on food prices in poorer nations. It should also be noted that many of those poor people are rural poor trying to eke out a living from the land. Trying to keep grain prices low hurts them and also decreases their incentive to grow food locally.

It’s an interrelated world. You can’t have cheap food and elevated oil prices, at least not for the long term.

KevinHurshisaconsultingagrologistandfarmerbasedinSaskatoon.Hecanbereachedat [email protected]

———

Sowhileitmightbea short-termfix,cutting Americanethanol productionwouldn’t likelyhavealong-term dampeningeffectonfood pricesinpoorernations.