Not long ago, as the world grappled with the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a often repeated phrase that drove me wild: “These unprecedented times.”

In reality, we were seeing many parallels with previous plagues.

How about the howling mob that surrounded a Montreal health office after mandatory vaccinations were announced, fueled by rumours that mothers were being tied down while their children forcibly got the jab. That was 1885. The disease was smallpox.

Read Also

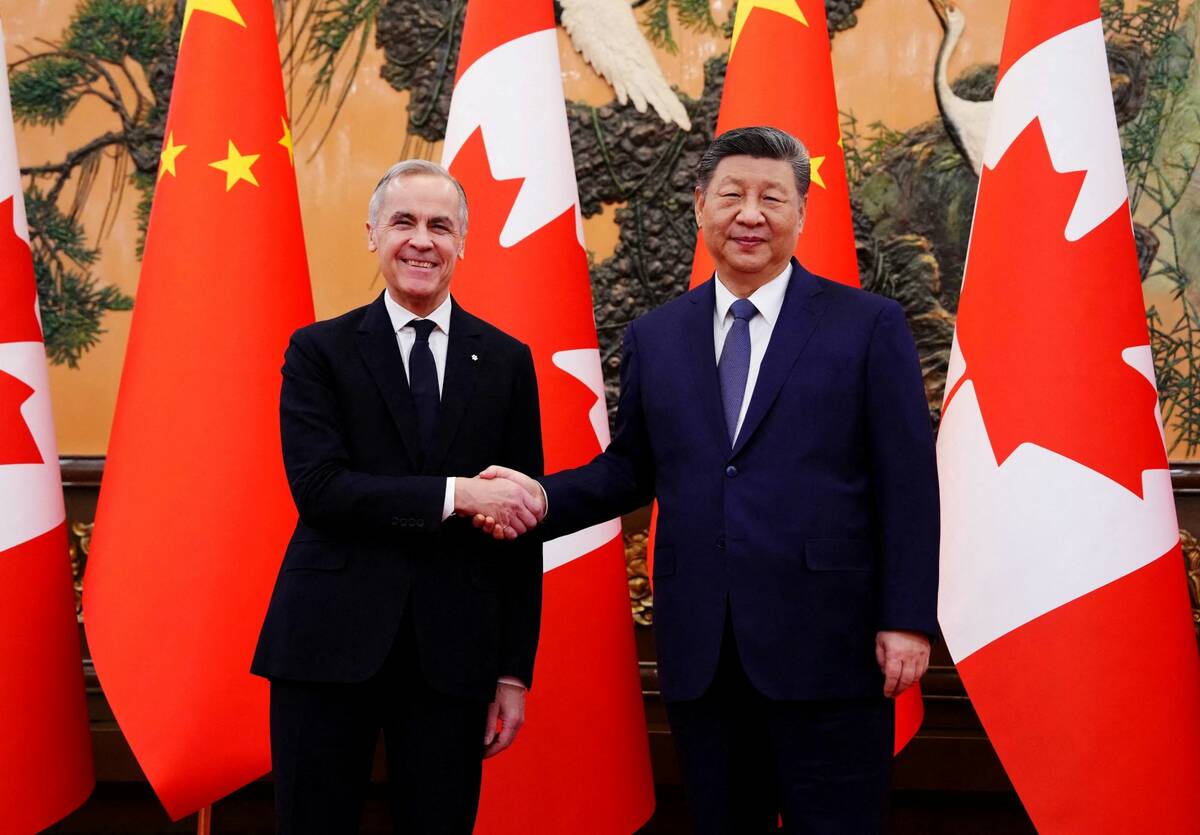

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

Today, the “unprecedented” news items are about United States President Donald Trump and his threatened tariffs (now delayed until March), but it’s not the first time Canada has had to deal with a wave of protectionism.

Post-Second World War America was a happening place. Their economy was booming.

“There was nobody to challenge them,” according to Bruce Muirhead, a professor of history at the University of Waterloo and chair of public policy with Egg Farmers of Canada.

As European nations rebuilt their economies, U.S. dominance waned. The Canadian economy gained strength as our manufacturing sector ramped up.

In 1964, John F. Kennedy’s administration enacted the Interest Equalization Tax (IET). According to government documents from the time, U.S. citizens who invested in foreign stock or debt would be subject to a tax ranging from 2.75 to 15 per cent.

Muirhead explained that Canadian borrowing (and borrowing from other countries) was siphoning U.S. dollars out of the market and pressuring the Amerian exchange rate. The IET was supposed to slow that down by raising the cost of borrowing.

“They [were] attempting to deal with the changing world,” he said.

The ruling classes of the U.S. and Canada were much more buddy-buddy then than now, Muirhead noted. Ottawa dispatched someone to Washington and the Americans gave us an exemption.

Fast forward to the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. While not in dire economic straits, the American populace was suffering from a “psyche of depression,” Muirhead said.

He recalled how, as a boy in his uncle’s Vermont backyard, some of the adults bemoaned the state of the economy, how the Japanese were eating their economic lunch, and how “the U.S. is done.”

The U.S., its dollar being the reserve currency of the world while backstopping the gold standard, couldn’t devalue its currency relative to other currencies, wrote economics professor Douglas A. Irwin in a 2013 paper. Other countries could devalue their currencies and gain a competitive advantage for their export sectors.

European and Japanese manufacturers were becoming a serious competitive threat to major U.S. industries, Irwin wrote.

The Nixon administration, playing off the sense that the U.S. was being taken advantage of, instituted new economic policies designed to force other countries to revalue their currencies. This included detangling the U.S. dollar from the gold standard once and for all, as well as a 10 per cent tariff on a bit more than half of imported goods.

Once again, Canada went to the U.S., unsuccessfully this time, for leniency.

Nixon framed the U.S. coming off the gold standard as an attack on foreign irresponsibility that was threatening global stability. It also appears Nixon wasn’t impressed with the elder Trudeau. Recordings from the oval office revealed Nixon had called him a “pompous egghead” after a meeting in late 1971, as per a 2008 report from CBC.

An abrasive president, tensions with a Trudeau and presidential messaging around foreign irresponsibility should all sound familiar.

The economic measures were initially well-received by the American public, wrote Jennifer Levin Bonder in a 2018 article for the Institute for Research on Public Policy but, in the end, the tariffs only lasted four months.

In the meantime, Americans realized that by putting tariffs on the raw goods entering the country, consumer goods became more expensive, Muirhead said.

The tariffs didn’t last long enough for meaningful restructuring of Canadian industry, he added. Canada did, however, look toward trade diversification, namely with Europe and Japan, Levin Bonder wrote.

Muirhead noted common themes between the early ‘60s and present day. The U.S. finds its prestige and power on the world stage dwindling. It feels hard done by and reflexes into protectionism.

The difference this time around, said Muirhead, is that Trump’s administration appears to be backed by a strong ideological agenda. Ideology and reason don’t always go hand in hand, as seen by the the confusion of some Americans when told they’ll be the ones paying the tariffs.

Finding parallels between the present and past protectionism won’t make trade wars easier to live through. However, forgetting the past leaves us open to unhelpful and hyperbolic rhetoric from those who stand to gain from public fear and confusion.