An excerpt from “Removal of the Canadian Wheat Board monopoly: Future changes for farmers and the grain industry,” published by the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. The paper says change would have advantages, but a voluntary CWB would have challenges. The full report is at www.fcpp.org.

A voluntary board could be organized according to a number of business models.

First, it could be a full-fledged farmer grain company (with assets), or a co-operative. It would be owned by farmers, possibly with a personal investment in it. But it would likely need to have around 10-20 per cent or more of the Western Canada grain-handling market in order to have sufficient economies of scale and low enough costs to compete with private-sector firms.

Read Also

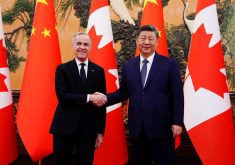

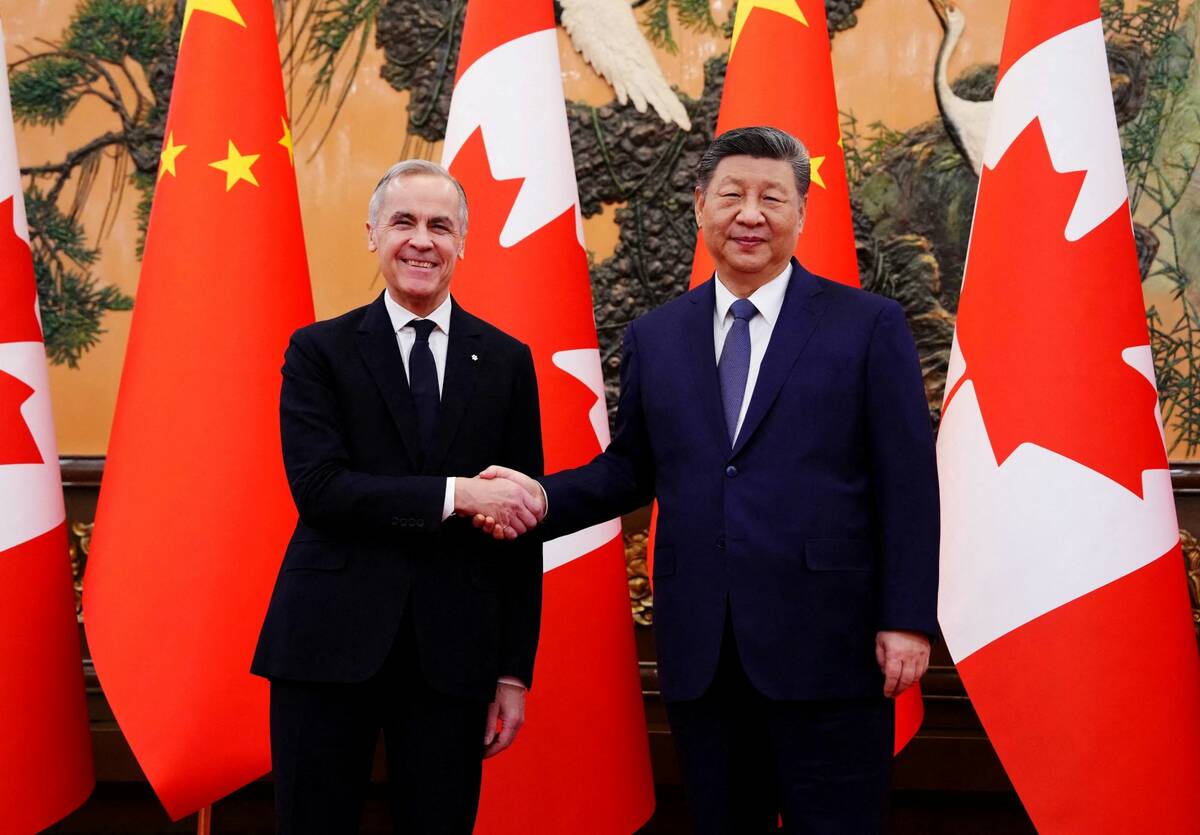

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

However, it may have trouble raising enough capital to obtain sufficient assets, though it would likely inherit some assets from the board. The three Prairie pool co-operatives and UGG had tried this model for many years, and all failed to remain as independent grain firms, and so it is unclear if this model would succeed for a voluntary board.

A second model, a full-fledged grain exporter (with assets) is another possibility for the voluntary board. However, about 15 private grain firms are accredited exporters of grain and engaged by the wheat board monopoly to export grain, and so a grain exporter that is a voluntary board may face considerable competition.

A number of the largest exporters already have substantial assets, including ships and port access, and inland elevators, and are very experienced in exporting. Currently the accredited exporters account for up to half of all board grains exported.

Therefore a voluntary board may find it difficult to compete against the existing exporters, especially if it is unable to acquire enough assets, or make suitable agreements to access the assets of other firms (e. g. elevators, port terminals, ships).

A third model, a grain broker (without assets), is another possible approach for a voluntary board. Grain could be purchased from farmers, from grain companies, and resold to other grain companies, or exported. However, it is unclear how well the grain broker model without assets would work, when competing against full-fledged grain companies with ample assets both at port and inland.

Also, it is unclear how much additional demand there would be for a large grain broker, as there are already a number of experienced grain brokers in operation in non-board grains, and profit margins may be relatively thin.

It is also unclear what advantage a voluntary board grain broker would have over existing grain brokers in dealing with farmers, who already have farmer customer contacts and loyalty through non-board grains. (One similar alternative is a grain reseller without assets, which is similar to a grain broker, except that a grain reseller takes ownership of the grain while a broker does not.)

However, given the above three models, each with its possible limitations, it will take considerable analysis and thought to determine which model may be most likely to succeed for a voluntary board.

Milton Boyd is an economist at the University of Manitoba.

———

ThethreePrairiepool co-operativesandUGG hadtriedthismodel formanyyears,and allfailedtoremain asindependentgrain firms…