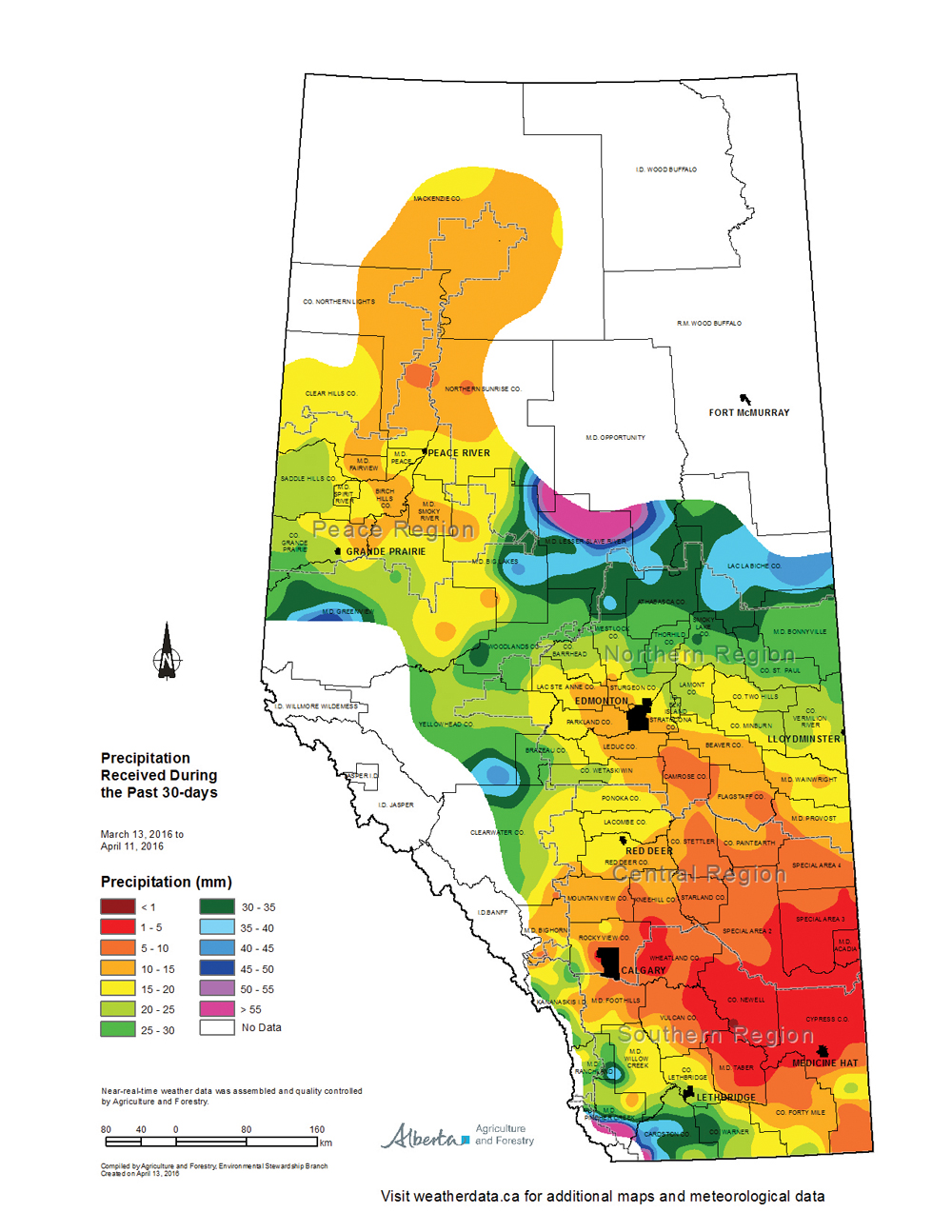

With a pretty warm first half of April across Alberta I won’t be surprised if we end up seeing an early start to thunderstorm season. So I figured that maybe we should have an early start to my annual look at thunderstorms.

To begin with, we’ll need to talk about one of my weather pet peeves, which is when people mix up weather watches and weather warnings. Basically, when we are talking about thunderstorms, a severe thunderstorm watch is when the potential exists for severe thunderstorms to occur. This means that severe thunderstorms have not yet formed. There may be some thunderstorms around, and you need to be wary of them, but so far none of them has become severe.

Read Also

Thunderstorms and straight-line winds

Weather columnist Daniel Bezte discusses the strength of straight-line winds during a thunderstorm and the damage they can cause.

A severe thunderstorm warning means severe thunderstorms have developed and conditions, which meet the severe criteria, have been recorded either directly by observers or by radar. When you hear a warning, it means you need to take immediate precautions.

Severe thunderstorm watches are typically issued when all of the ingredients for severe storms are in place, but forecasters are not sure where, or sometimes even if, thunderstorms will develop. An analogy you can use is a pot of water on the stove. If you turn on an element, put on a pot of water, eventually it will boil, but the big question is: Where will that first bubble form and break away from the bottom of the pot? That would be our thunderstorm, you knew it was going to form, determining exactly where was the hard part.

So, just what ingredients are required for a severe thunderstorm?

First of all you need rising air, and to get that you need heat, or rather, you need a large difference in temperature between two areas. There are a couple of ways you can achieve this difference in temperature. One way most people are familiar with is to have a very hot day. But just having a very hot day does not mean that there is a large difference in temperature. To get thunderstorms on a hot day, you need to have cool air aloft (up above the ground).

When this occurs, the hot air at the surface begins to rise and encounters cool air as it continue to rise. This means that our rising air will remain warmer than the air around it and will continue to rise. The cooler the air around it, the faster it goes up, the faster it goes up, the stronger the storm (typically).

Now, sometimes we can get severe thunderstorms when we don’t have particularly warm air at the surface. Two different scenarios can play out when this happens that can still lead to severe thunderstorms. In the first scenario, there is very warm air a few thousand feet up from the ground. This warm air then has cold air above it, and just like the hot day on the ground this warm air in the upper atmosphere can rise up giving us elevated thunderstorms.

The second scenario is when there is a strong contrast of warm and cool air at the surface, or in other words, we have some type of front cutting through an area. On one side of the front it is cool and on the other side it is warm. The cold air acts like a wedge and forces the warm air up. Sometimes this occurs when a cold front is moving into an area, so the day starts off warm and then the cold air pushes in, lifting the warm air up in front of it and giving us thunderstorms. The other way is when warm air is moving into a region. The day starts off cool and then storms develop as the warm air rises up over the cool air as it moves into the region.

Now, simply having a big difference in temperatures will not give you a thunderstorm, or at least, will not give you a severe thunderstorm. There are still a couple more ingredients needed.

The next key ingredient is water vapour, or humidity. It takes energy to evaporate water, so the more water vapour there is in the air the more potential energy there is. Our rising air is cooling as it rises, but not as fast as the air around it, so it continues to rise. Then, condensation starts taking place, which releases heat into the air. This makes our rising air even warmer than the air around it, so it rises even faster. If you have air continually rising up, eventually the amount of air accumulating up at the top of the storm will become so great that it just has to fall back down again, wiping out the storm in the process. To get around this problem we need some kind of vent at the top of the storm that takes away all of the rising air that is accumulating there. We need a strong jet stream of air over top of the storm to help “suck” away the accumulating air.

Now we have the key ingredients for a severe storm, but like any good chef, Mother Nature has additional ingredients she can use to make some storms truly awesome. We’ll have a look at those and gentle garden-variety thunderstorms in May.