Glacier FarmMedia – Let’s continue our look at severe summer weather by examining heat waves.

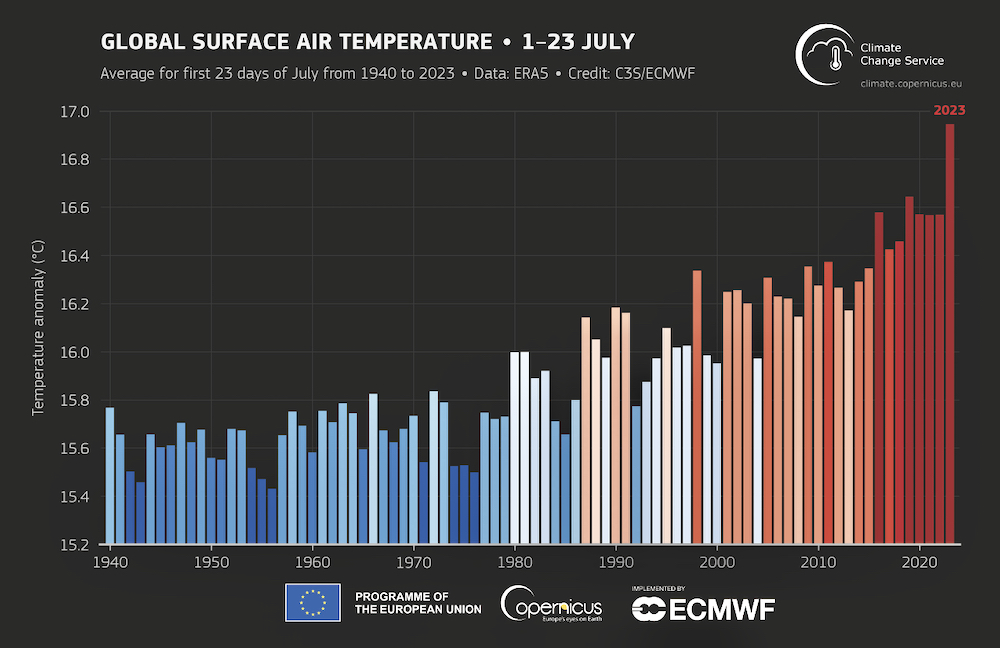

While we have seen recent hot weather, it pales in comparison to some of the extreme heat reported in other parts of our planet this July.

Heat waves have enveloped large portions of the Northern Hemisphere, bringing record-breaking heat to parts of North America, Europe and Asia. In California, Saratoga Springs hit 53.9 C on July 16, tying for the sixth-hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth.

Read Also

How Earth evens out the energy input

Earth has surpluses of radiation in its equatorial regions, and deficits toward its poles. Our weather is a matter of Earth trying to even out the imbalance, Daniel Bezte writes.

China may have smashed its all-time high with a reading of 52.2 C on July 17 in the township of Sanbao. The previous record high was 50.5 C. Should this reading be confirmed, it will also break the record of the hottest temperature ever recorded north of the 40th parallel.

All this heat appears to have pushed the Earth’s average temperature above 17 C for the first time in recorded history. This first happened on July 3 this year, and it has been above this value for nine days since.

I could go on, but let’s just say that, with a well-established El Niño now in place, the stored heat being released into the atmosphere will continue to drive record-breaking temperatures in coming months.

Bringing the heat

What is the meteorology behind heat waves?

To start, we should first define a heat wave is and note the criteria Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) uses to define heat events.

The best definition I could find is “an extended period of unusually high atmosphere-related heat stress, which causes temporary modifications in lifestyle and which may have adverse health consequences for the affected population.

“Thus, although a heat wave is a meteorological event, it cannot be assessed without reference to human impacts.”

That’s from “On the Definition of a Heat Wave” by Peter J. Robinson, a professor of geography at the University of North Carolina.

It basically means that, while a heat wave involves abnormally warm temperatures, the impact on people is key.

This is why, if you check ECCC’s website for a list of criteria for public weather alerts, you find several different heat-related alerts for the Prairie provinces.

In southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan, a heat warning or advisory is issued when two or more consecutive day-time highs are expected to reach 32 C or warmer and night-time lows are expected to remain at or above 16 C. Alternatively, an alert is issued when there are two or more consecutive days of expected humidex values reaching 38 C or higher.

Southern Alberta has the same criteria as southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan, but without the mention of humidex values because this region rarely sees high humidity.

Over more northern regions, for Manitoba the threshold is two or more days with day-time highs warmer than 29 C (and 16 C or warmer at night) or humidex values greater than 34 C. In northern Saskatchewan and Alberta, the bar is set at 29 C during the day and 14 C at night.

The roots

There are several scenarios that can come together to give us the conditions prompting a heat warning, but let’s look at the conditions that lead to big, long-lasting heat waves.

That type of intense, record-breaking heat wave requires several meteorological events.

First, we usually need a blocking pattern to develop, and the most typical pattern is the Omega block. This pattern has upper-level lows sitting to our west and east, with a ridge of high pressure in the middle.

This is important because this pattern, as the name suggests, can become fairly stable and tends to sit in one place for several days.

The ridge of high pressure allows a few of things to happen. First, the descending air inhibits the growth of clouds. This means plenty of sunshine and, in the summer, sunshine means heat.

On their own, however, sunny skies do not mean a heat wave. The next part has to do with the strength of the high. When the high is strong, we get very strong subsidence, or sinking of air. As this air is pushed downward, it hits the ground and is compressed.

Anyone who has used an air compressor or a hand pump knows that as you compress air, you force air particles closer together. This increases the rate of particle collisions and these collisions transfer energy, which we feel as heat.

Grab a bike pump, give it 20 or so pumps and then feel the bottom. It’s hot due to the compression of air.

So, when there is a strong ridge of high pressure above, the compression of sinking air can dramatically heat that air and give us some truly warm days.

If the upper high is not that warm, all this compression and heating of air won’t do much to give us record-breaking temperatures. If the upper high is warm to begin with, compression combined with additional heating of the sun pushes temperatures up.

The big question is not whether we will see a heat wave across our region, but rather when we will see it. Looking at the longer-range forecasts, there are signs of a building heat wave around the middle of August.

That is a long way off and plenty can and will happen between now and then, so keep checking and watch the forecast.

– This article was originally published at the Manitoba Co-operator.