As summer works its way back into our region it’s time to pick up where we left off in our discussion of severe summer weather. In this article we’ll look at how we can predict which direction a thunderstorm might be moving.

Trying to figure out just how intense and which direction a thunderstorm is moving can be pretty tough if you have to base it on observation only. But with some background knowledge, you can make some pretty good assumptions.

First of all, let’s look at how thunderstorms tend to move. We live in the part of the world that has predominantly westerly winds, especially at high altitudes. This is an important point when it comes to thunderstorms.

Read Also

Thunderstorms and straight-line winds

Weather columnist Daniel Bezte discusses the strength of straight-line winds during a thunderstorm and the damage they can cause.

When we look at a thunderstorm, it usually covers a relatively small area of land, at least compared to general areas of low pressure and winter storms. That said, thunderstorms cover a very large area when we look at them from a vertical perspective.

A typical area of low pressure or winter storm will usually have clouds that extend from around 3,000 feet upwards to around 15,000 feet (usually much lower than this). In a thunderstorm, we can see clouds starting around the same height, but they can extend upwards as high as 50,000 feet. We rarely see thunderstorms that tower this high in Alberta, but it isn’t uncommon to have thunderstorms that are pushing between 30,000 and 40,000 feet.

OK, so now we know that thunderstorms can reach very high altitudes, what does this have to do with the direction of a thunderstorm’s movement?

Well, I guess what really bothers me when a thunderstorm is developing nearby, is when someone says “don’t worry it’s going to miss us, the wind is from ‘x’ direction.”

Surface winds may or may not have any impact on a storm’s direction of movement. In fact, if I had to put money on it, I would probably bet against it almost every time. We need to remember that thunderstorms are regions of rapidly rising air. Kind of think of it like a vacuum, the storm is pulling air upwards, which means air all around the storm will be pulled in towards it.

Every thunderstorm is different and there can be many things that will affect how air moves into a storm. But I think it is fairly safe to say that direction of the surface winds, especially when the storm is fairly close to us, will have little effect on the storm’s direction. It is the wind higher up in the atmosphere that largely controls storm direction.

Remember, these storms go way up into the atmosphere, often reaching the top of the troposphere or weather-creating regions. This means that the air flow high up tends to control the movement of the storm and these winds are usually westerly.

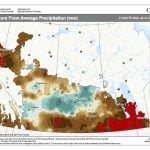

Unfortunately, it isn’t always as easy as this, since we have all probably experienced thunderstorms coming from directions other than westerly. Due to the long wave patterns in the westerly flow of the upper levels of the atmosphere, these westerly winds can be bent so that they are blowing pretty much any direction. If we were to go with the statistics of wind direction in the upper atmosphere, we would find that most of the time, the wind is blowing from somewhere between southwest and northwest.

Occasionally we will see these winds blow from the north or south, and even less often from the southeast or northeast. Easterly winds are extremely rare, so the chances of seeing a thunderstorm coming from the east are very small indeed!

But wait, you have seen a thunderstorm that came from the east? Well, it might have happened, but more than likely the storm didn’t come from the east, but rather, the storm grew from the east. The growth of thunderstorms can be explosive to say the least.

Within a 10- to 20-minute period a thunderstorm can grow from a few square kilometers to hundreds or even thousands of square kilometres. If a developing storm is not moving very fast from west to east, and you were close to it, say it was 25 km to your east, that storm could grow rapidly spreading out in all directions. This would make it appear that it was coming from the east even though it is slowly moving away from you.

So how does all of this help you determine which direction a storm is coming from?

If the storm is in a general westerly direction from you, then you should be concerned. Otherwise you need to be observant and see which direction the higher clouds are or have been moving, and be aware that the growth of a storm can mask the overall movement of the storm. You can also watch the top of the storm or nearby storms, to see which direction the anvil or wispy clouds are being blown off of the top of the storm. This will give you some insight into the direction of the upper level winds.

Next issue we’ll look at how you can determine the intensity of a storm through observation.