The economic fallout from the pandemic could put fresh wind into the sails of protectionists, say industry officials here.

“Generally speaking, the sense is that protectionist policies and measures are here to stay,” said Greg Cherewyk, president of Pulse Canada.

“There will be a point where we revert back to a more or less normal trading environment, but it’s also reasonable to assume that the actions in response to food security concerns will have a lasting impact.”

Read Also

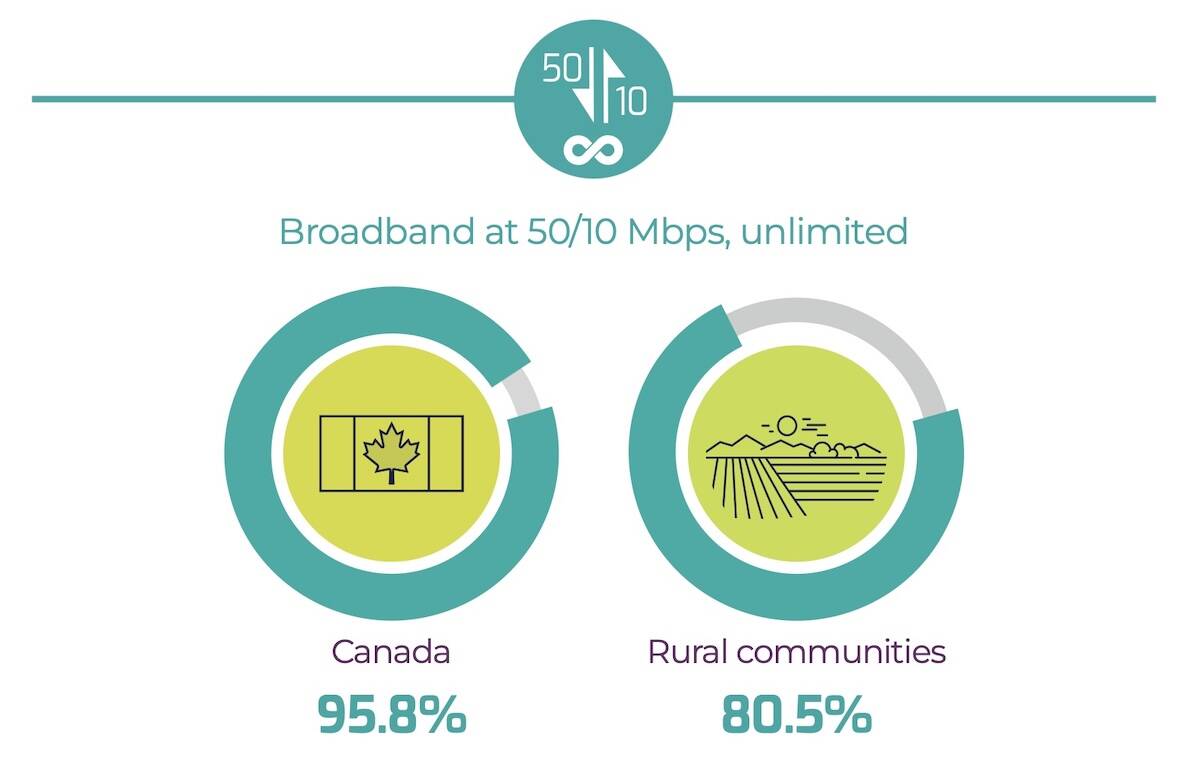

Rural Alberta gets further boost to internet connectivity

The province and feds join forces to help remote/rural Albertans get connected to reliable high-speed internet through its Broadband Strategy.

Trade barriers have already hit Canadian producers in recent years, including Italy adopting country-of-origin labelling on durum, China supposedly finding residue or pests in canola, and India slapping tariffs on pulses.

But the pandemic has seen new measures arise such as Sri Lanka banning imports of many foods and consumer goods in order to protect its currency because of a debt crisis. As well, some exporters, such as Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and Vietnam, have limited or halted exports of staples like wheat and rice.

“We are seeing the short-term policy decisions that are responsive and reactive to food security concerns,” said Cherewyk. “All of those actions that are being taken in response to these extreme conditions countries are facing create uncertainty. They increase risk for everybody involved in that global food supply chain.”

Cereals Canada president Cam Dahl said he fears an escalation in measures that hamper trade.

“We saw significant growth of economic nationalism with protectionist policies, and I’m quite concerned that that’s something we’re going to see going forward — countries using sanitary and phytosanitary measures that aren’t based on science to block trade,” Dahl said last month.

“There are countries that are looking at food security issues and thinking internal protectionism is a way to solve those issues. That will only add to the difficulties.

“I see market access as one of the largest threats going forward.”

While some developments, like the limit on grain exports from the Black Sea, might create some short-lived opportunities for Canada, “all of these short-term extreme measures that are being put in place really aren’t positive in the long term,” said Cherewyk.

“Any actions that you take to restrict imports or exports of food and feed just undermine the global food system,” he said. “It’s very unlikely that the effect of any of those short-term measures would be positive on our industry. We believe that the open and free trade of food and feed products is in everyone’s best interest.”

Canada’s hard-hit beef industry needs open trade, said Fawn Jackson, director of government and international relations for Canada Beef.

“We are an export-focused industry,” said Jackson. “We consume domestically 50 per cent and export the other half. So we’re going to do everything we can to talk about the importance of international trade.”

Foreign markets are also vital for selling different cuts and byproducts such as offal and hides.

“What we eat here in Canada isn’t necessarily what they prefer in other parts of the world, and getting those different cuts is what makes it financially viable for farmers,” she said. “It adds over $600 a head to the animal than if we just sold it in Canada.”

The bottom line is that trade is critical for Canadian agriculture, said Dahl.

“We depend on trade. There’s no other way of putting it,” he said. “The viability of Canadian agriculture depends on access to international markets. That needs to be a primary focus of governments.”