Pulse processing on the Prairies has come a long way, but there’s still a long way to go — especially here in Alberta.

“If you’d asked me 10 years ago, I would have said, ‘Ten years from now, we shouldn’t be shipping yellow peas away.’ And here we are, still fractionating far too large a percentage of it in China,” said Allison Ammeter, a pulse grower and prominent champion of the increasingly popular food legumes.

“It’s almost a mystery why more is not happening on the Canadian Prairies.”

Read Also

Best before doesn’t mean bad after

Best before dates are not expiry dates, and the confusion often leads to plenty of food waste.

And much of what is happening is taking place in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, not here.

The world’s largest pea-processing plant — French company Roquette’s $600-million facility in Portage la Prairie, Man. — is currently in startup mode. When fully operational, it will process 125,000 tonnes of peas annually. An hour’s drive to the east, Merit Functional Foods recently completed $150-million processing plant in Winnipeg, will use 25,000 tonnes of peas and canola annually. And it is designed to up that fourfold if the plant protein market continues to grow as it has. And near Saskatoon, Verdient Foods (now fully owned by global ingredient company Ingredion) is expanding its processing facility and expects to be using 100,000 tonnes of pulses annually.

Those plants could have — should have — been in Alberta, said Ammeter.

“I personally do not think the Alberta government has been nearly a good enough cheerleader, or we would have got Roquette or Merit,” said the Sylvan Lake producer.

“Those guys shopped around to all of the different provinces. They didn’t go to one place and then say, ‘We want to build at Portage la Prairie.’ They went to everybody and shopped it around.

“I truly believe that if the Alberta government had been a bit more aggressive and a bit more of a promoter, we would have it.”

‘Opportunity ahead’

But another view is that these are early days — and the biggest prize is not fractionation (breaking down pulses into protein, starch and fibre) but further processing and, ultimately, making food products with those ingredients.

“When you look at the grand scheme of things, five years in the history of pulse crops in Canada isn’t that long. Being two or three years later isn’t that long,” said Norm Janssen, former investment attraction manager for Alberta Agriculture who is now a business consultant.

“We may be a little late to the dance, but there are still some great opportunities to be had here. I really see the opportunity is ahead of us — I don’t think we need to focus on looking back to why we weren’t first or second.”

In Janssen’s view, further processing of pulse fractions sets the stage for food companies to set up shop here.

He points to Lovingly Made Ingredients — the ingredient-manufacturing arm of the British company Meatless Farm, which opened its 33,000-square-foot facility in Calgary in April — as an example of that.

“With companies like Lovingly Made Ingredients, we’re seeing in Alberta some further processing of these proteins, and I think from that will come the processing of food products,” he said.

“I think that’s where the opportunities are. Now that we can do all segments of plant-based food production — from growing to fractionation to texturizing to food production — there’s huge opportunity here.”

Ammeter agrees.

“I think we’ve put so much focus on the fractionation part that we’ve sort of missed the big picture, which is what happens when you get those ingredients being produced in Alberta,” she said.

“The goal is not having one secondary processor. The goal is having a cluster of businesses that show up because we’ve got a major processing plant. That’s what I’m excited about — all the tertiary processing that’s going to spring up once we get these secondary processors going.”

That’s starting to happen in Alberta already, said Kevin McGeough, CEO of More Than Protein Ingredients in Bowden.

“On the food-manufacturing side, we’re seeing a lot of companies that are coming into production and manufacturing different foods,” he said. “In plant-based foods, my last count was 35-plus companies that are in the process of setting up and establishing some sort of food manufacturing. I think that’s a really good sign.”

The payoff for growers

But while Janssen views the pulse-processing sector in western Canadian terms (“There is no magical line on that border between Saskatchewan and Alberta,” he said), distance matters when it comes to the purchase of crops.

For example, Roquette will pay premiums for its peas and is providing agronomic support for farmers. But it’s only buying from growers in Manitoba and southeastern Saskatchewan.

More Than Protein Ingredients has announced it will start construction on its $100-mlion wet fractionation facility at Bowden in spring with a fall 2023 completion date. The facility is the dream of Chris Chivilo, whose company, W.A. Grain & Pulse Solutions, went into receivership in May. The project is now moving forward under More Than Protein Ingredients, with McGeough moving from a consultant’s role to CEO and Chivilo back on board as chief operating officer. The company says it has lined up new investors but hasn’t disclosed who they are other than none are from Alberta.

Attracting investors is a huge challenge, said Ammeter.

“It is really tough to put together enough dollars for a large venture,” she said. “That’s the biggest hurdle we have to work through: How does a relatively nascent industry like plant protein attract venture capitalists that don’t want to take a lot of chances?

“The plant in Bowden has scraped back dirt, but there’s nothing being fractionated yet. There’s a plant in Lethbridge that’s so close, but they still need funding. It all comes down to that investment.”

Both Ammeter and McGeough are critical of the provincial government for not doing more to attract pulse processing to Alberta.

“I would have liked to see the government 100 per cent behind us,” said Ammeter, former chair of the now-defunct Plant Protein Alliance of Alberta, an organization created to attract plant-protein processing here. “We had so much support within the industry that supports plant proteins. The only thing we had difficulty with was getting the complete support of the government. We always felt like we were trying to drag them along kicking and screaming.”

Moving ahead

It’s not just about offering grants or tax breaks, she added.

“From what I understand, it wasn’t really a matter of a lot of money changing hands that made investors choose Saskatchewan and Manitoba. It was a matter of them making it easy,” she said. “In the case of Roquette, we heard how the Manitoba government brought together a team in one room — everybody they could possibly need to talk to.

“Whereas I heard about the Alberta government saying, ‘You should go talk to so-and-so about that.’ These guys aren’t going to come over from France to be told to go talk to so-and-so. They want it to be easy. I think we can do more in Alberta to really cheerlead our province. I really believe that.”

The Plant Protein Alliance of Alberta was created to be part of such an effort. Its main focus was to bring different players together to both build excitement and help potential partners and allies connect with one another. But in March, the provincial Ag Ministry abruptly cancelled its $250,000 operating grant.

However a new ag minister, Nate Horner, was appointed in November. McGeough hopes Horner (who has had rural economic development added to his ministry) will bring a new push for pulse processing in the province.

“There’s a long ways to go. We’re really just passing the formation stage into the rapid growth stage of the market,” he said. “We’re on full tilt, and we hope the provincial government recognizes the importance of this type of industry and comes in strong in terms of support.”

And the time is now, said Ammeter.

“Lovingly Made is here because their European counterparts recognize that their carbon footprint would be smaller if they parked themselves close to where it’s grown,” said Ammeter. “But they’re not winning that battle yet, because they’re not using Alberta yellow peas fractionated in Alberta.”

And Alberta grows a lot of peas.

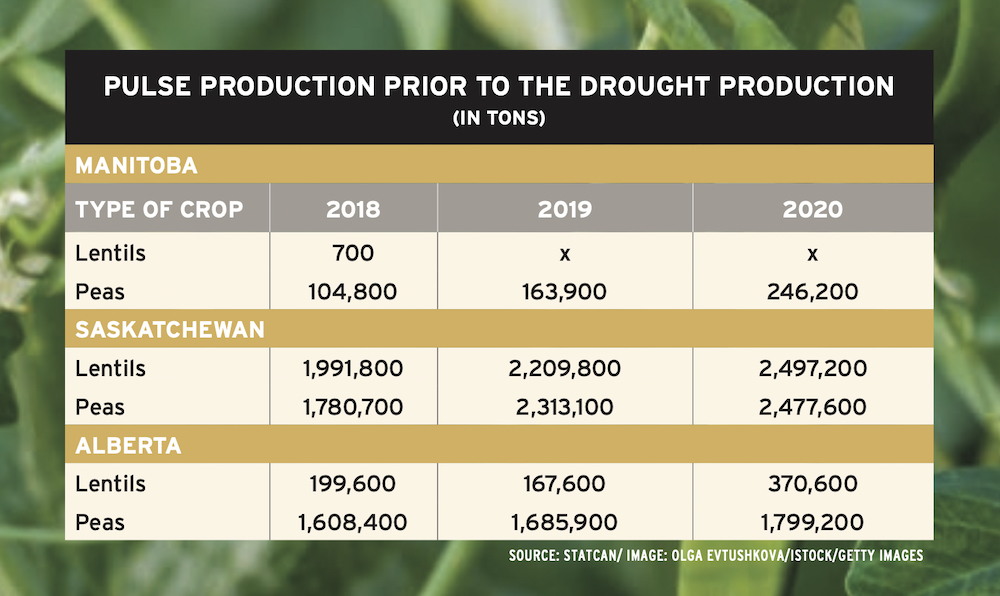

Saskatchewan is the biggest producer (harvesting 2.5 million tonnes in 2020) but Alberta isn’t far behind (1.8 million tonnes in 2020 with both provinces seeing production halved by the drought this year). Manitoba — home to Roquette’s huge facility — was far behind at just 246,000 tonnes.

But Janssen looks at what could be done with Alberta’s huge crop.

“There’s many advantages that we have, and despite stepping into it at a slower pace, I think there’s going to be some really good opportunities,” he said.