Most of us would agree that farming and ranching run on partnership more than paperwork. Often, that partnership is marriage.

But for decades, the law didn’t always recognize it. The 1975 Supreme Court of Canada decision in Murdoch v. Murdoch showed a glaring gap between the realities of ranch life and property law. The case didn’t just reshape legislation — it challenged how Canadians understood marriage, labour and fairness on agricultural operations.

The ruling involved the divorce of Irene and James “Alex” Murdoch, Alberta ranchers whose decades of joint work built a substantial operation. Murdoch v. Murdoch (1973 CanLII 193, [1975] SCR 423) remains one of the most influential family property cases in Canadian history.

Read Also

Lacombe research centre closure called ‘catastrophe’

Cattle industry mourns loss of Agriculture Canada’s research centre included in sweeping cuts that were announced late last month.

What happened

Irene and Alex Murdoch spent more than 20 years building a sizable cattle operation in southern Alberta. Married in 1943, they started as hired workers before gradually acquiring ranch land, buying, selling and improving multiple properties over about 15 years. Ranching was their main livelihood, and Irene played a key role. At trial, she described her work:

“Haying, raking, swathing, moving, driving trucks and tractors and teams, quieting horses, taking cattle … dehorning, vaccinating, branding … anything that was to be done … I worked outside with him, just as a man would.”

For months each year, when Alex worked elsewhere, Irene managed the ranch alone. She also contributed financially, using money from her mother for household essentials and, at times, for ranch purchases. Despite her efforts, legal ownership remained solely in Alex’s name — a common practice for that era.

When Irene and Alex Murdoch’s marriage ended, she argued that her decades of work entitled her to a rightful share, even though the land and assets were in Alex’s name. In 1975, the Supreme Court of Canada rejected her claim in a 4–1 decision. Justice Willard McIntyre wrote:

“The work which Mrs. Murdoch performed was the sort of work that many ranch wives do. … There is nothing to show any common intention that the property was to be held jointly. … The respondent’s contributions, while no doubt of value to the marriage, do not establish a beneficial interest in the property.”

One judge strongly disagreed. Chief Justice Bora Laskin argued that Irene Murdoch’s decades of work on the ranch created a rightful interest. He wrote:

“In making the substantial contribution of physical labour, as well as a financial contribution … the wife has … established a right to an interest which it would be inequitable to deny and which, if denied, would result in the unjust enrichment of her husband.”

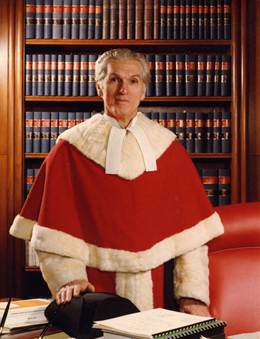

Chief Justice Bora Laskin

Supreme Court of Canada

Image courtesy Supreme Court of Canada

Laskin emphasized that formal agreements were not required for fairness: “The appropriate mechanism … is the constructive trust which does not depend on evidence of intention.”

Laskin’s dissent highlighted a truth familiar to ranch families: marriage in agriculture is an economic partnership, whether the paperwork shows it or not.

Public outcry and legal shift

The Murdoch decision caused a national uproar. Canadian farm and ranch women were shocked that someone who had spent decades working on a ranch could legally walk away with nothing. The National Council of Women declared: “No woman should be left with nothing after a lifetime of labour simply because her name is not on a title.” Newspapers, women’s groups and commentators widely criticized the ruling, highlighting the invisible work that keeps farms and ranches running.

Chief Justice Laskin’s dissent encouraged a rethink of how the law treats contributions in marriage. Five years later, the Supreme Court of Canada in another case Pettkus v. Becker, 1980, affirmed “a person who has been enriched by the efforts of another … must provide restitution,” establishing that labour and non-financial contributions could at last create enforceable claims.

Legislatures responded as well. Alberta introduced the Matrimonial Property Act in 1978 (now the Family Property Act), formally recognizing both spouses’ contributions, even unpaid work. Other provinces followed suit. During one such legislative debate, Alberta’s attorney general Merv Leitch explained:

“Murdoch showed us that the law, as it stood, did not adequately protect the contributions of married women.”

These reforms introduced what are now standard principles:

- shared ownership of marital property,

- recognition of household and farm labour,

- protection for spouses not on title, and

- presumptive equal division of assets.

What this means for farmers and ranchers today

Murdoch v. Murdoch clearly identified the risk for farm and ranch families when one spouse works extensively “off title.”

Clearly, much work and reform were needed, as the law had historically overlooked invisible work — a significant aspect of the Murdoch critique and the reason for reform. In 2017, the Nova Scotia Law Reform Commission stated:

“Contributions through household management and child-raising … were not treated as relevant contributions giving rise to a presumption of resulting trust.”

Today, Alberta’s Family Property Act, as well as those of other provinces, provides a framework for dividing marital property, recognizing both financial and non-financial contributions — an essential shift from Irene Murdoch’s era.

Key points to note

Title isn’t everything. Even if land or equipment is in one spouse’s name, courts may recognize labour, management and improvements as part of marital property.

- Document contributions. Records of livestock care, haying, calving, equipment purchases, bookkeeping and household support can strengthen any future claim.

- Use formal agreements. Co-ownership arrangements, marriage contracts and partnership agreements can help prevent disputes, particularly when multiple generations work together.

- Plan for succession. Wills, trusts and farm transfer strategies help protect both the operation and fairness between spouses.

- Consider corporate structures carefully. Incorporation or partnership arrangements can affect property claims, so professional legal and accounting guidance is essential.

Courts now recognize that ranch work, administrative tasks, child care and household labour carry real economic value in property division. Assets acquired or enhanced during marriage — including land, livestock, equipment and income — are generally considered divisible. Spouses who are not on title are far less likely to leave a farm marriage with nothing, though clear agreements and planning remain essential.

Murdoch v. Murdoch reshaped Canadian family law in agriculture and serves as a reminder that every contribution to the farm or ranch, financial or otherwise, should be recognized, documented and safeguarded.

Bottom line

Although Irene Murdoch lost at the Supreme Court, she later received a lump-sum maintenance award of $65,000 during divorce proceedings — likely far less than the value of the ranch she had helped build.

Murdoch v. Murdoch helped reshape Canadian family law protections to ensure that spouses who pour their time and effort into agricultural operations are recognized as true partners.

Today’s fairer, more predictable matrimonial-property system exists partly because Irene Murdoch’s story showed Canadians what happens when the law fails to value the invisible, unpaid, but essential labour that keeps farms and ranches running.

Her loss changed everything.

Billi J. Miller is a published author, photographer and speaker from east-central Alberta. She writes from her home office. Read more history in her farm wives books.