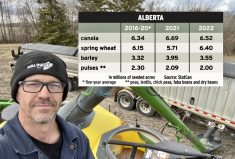

Glacier FarmMedia – The Indian government might have to consider opening a second window for duty-free yellow pea imports, according to a senior industry official from that country.

It could happen “maybe in the back end of the season,” Manek Gupta, managing director of Viterra India, said during a webinar hosted by the India Pulses and Grains Association (IPGA).

He believes there will be a sizeable shortfall in winter season chickpea production. Seeding of the crop was 10 per cent behind last year’s pace at the time of the Dec. 14 webinar.

Read Also

India likely to triple lentil import duty

Analysts anticipate India hiking duties to 30 per cent after March 31 to bolster domestic prices on expectation of strong harvest.

Gupta is forecasting a nine per cent drop in production, to about 11 million tonnes, but it could be worse than that if there is major heat stress in January or February.

Weather conditions for the current growing season have been average, but monsoon rainfall was disappointing in some key districts in the states of Karnataka and Maharashtra.

“There are these red flags, or orange flags at least, at this stage,” he said.

The Indian government previously dropped import restrictions on peas through to the end of March in reaction to predictions of a smaller chickpea crop.

“The expectation is that 400,000 to 600,000 tonnes of yellow peas will probably come in during this window, which will surely help alleviate the potential shortage of chickpeas,” said Gupta.

However, it is not expected to completely alleviate the estimated 1.21-million tonne drop in production, combined with tight carryout supplies from the previous year.

Australia is the only other potential relief valve. It is a major exporter of desi chickpeas, but the Australian government is forecasting an average crop of 533,000 tonnes and a carry-in of 263,000 tonnes.

Gupta thinks both those numbers will be lower than what the government anticipates.

The estimates would be enough for a 689,000-tonne export program, or about the same amount as last year. That will only be enough to sustain Australia’s usual customer base, which includes Pakistan and Bangladesh.

“The total export surplus out of Australia is not really going to be there to cater to the Indian market, even if the import duty was brought to zero,” said Gupta.

Based on that, he thinks the government of India may have to consider a second duty-free import window for yellow peas later in the 2023-24 campaign.

The government was expected to end 2023 with one million tonnes of chickpea stocks, down from 1.4 to 1.5 million tonnes at the start of the year. Given those numbers, it is expected to be a big buyer of the crop when chickpeas are harvested in April and May.

Other pulses

India’s lentil crop is faring better than its chickpeas. Farmers are expected to plant about 4.63 million acres, similar to last year. Crop conditions have been good so far.

“Some of the field surveys we hear about are projecting a slightly higher crop than last year,” said Gupta.

He is forecasting 1.65 million tonnes of production, up from 1.55 million tonnes last year.

The country will need those extra lentils. Consumption is up due to sky-high pigeon pea prices. Gupta estimates consumption of lentils increased by 250,000 to 300,000 tonnes in 2023 compared to the previous year. The demand led India to import 1.5 million tonnes of the crop in 2023, one of the highest programs on record.

Imports will probably soften slightly in 2024 due to improved domestic lentil production.

The government is a main buyer of the crop, recently purchasing about 500,000 tonnes from the trade, bringing its stocks to 650,000 tonnes.

Kharif or summer pigeon pea production is estimated at 3.42 million tonnes, similar to the previous year’s disappointing 3.31 million tonnes. Carry-in is a paltry 280,000 tonnes.

Ankush Jain, business head of pulses with Olam Agri India Pvt. Ltd., expects that India will import 900,000 to one million tonnes of pigeon peas to make up for the shortfall. That would leave only 70,000 tonnes of carryout at the end of December 2024, sparking government buying. The government has purchased 500,000 tonnes over recent months.

India also recently announced an extension on the duty-free import of lentils through March 31, 2025, which is good news for Canadian exporters of the crop.

Bimal Kothari, chair of the IPGA, would like to see India eventually move to a free-trade policy for pulses.

In the short-term, he thinks there should be a duty that raises the landed cost of imported pulses to India’s minimum support price for the crops. That would be a more predictable system than India’s current “knee jerk” policies that last for three months and cause headaches for exporters and importers.

The IPGA is also working with Brazil, Argentina and Australia to get farmers in those countries to consider growing pigeon peas to augment India’s sagging production.

– Sean Pratt is a reporter for The Western Producer.