Recent rainfall means farmers need to scout their crops and make decisions about spraying.

“Certainly the rain that we’ve had would get things going,” said Kelly Turkington, a plant pathologist at Agriculture Canada’s Lacombe research station.

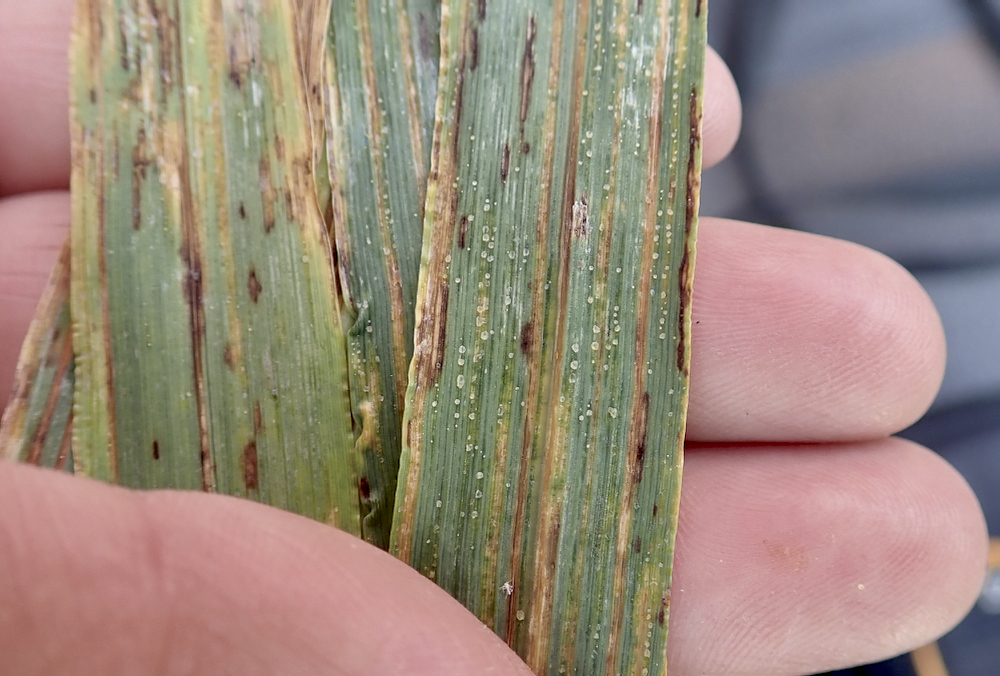

For example, leaf spot diseases in barley and wheat can quickly flare up, he said on July 13.

Read Also

Alberta farmer invited to World Economic Forum

Southern Albertan farmer’s regenerative agricultural practices featured on panels at Davos where nations come together in partnership.

“Within a week, it can start producing spores and infect the lower leaves and if the moisture continues, it’ll move up the canopy.”

Leaf spot diseases and fusarium head blight can cause late development, affecting grain filling, plumpness and bushel weight, especially in barley. However, the impact isn’t as dramatic when crops are further advanced, and other factors — the specific variety being grown, the farm’s area and the amount of rainfall — also affect severity.

However, some growers may want to reduce the risk by spraying an older, cheaper product that includes protection from fusarium head blight on the label, keeping in mind the pre-harvest intervals, said Turkington.

Checking the latest crop reports can also provide valuable information.

“We’ve been monitoring the rust situation like we do every year. I’m part of the Prairie Crop Disease Monitoring Network and we issue a weekly rust forecast,” he said. (It can be found at prairiecropdisease.blogspot.com)

“We look at rust development in the United States — so stripe rust in Washington State, Oregon, northwest Idaho and then that corridor from Texas to Nebraska.”

Since there is a drought stretching from Texas to Nebraska, there has been little disease development. Washington State did not have a lot of stripe rust development either, but in the first half of July there was an increase in rust reports in that state.

“That means there are spores available to be blown into Western Canada,” said Turkington. “The key risk areas are southern Alberta, central Alberta and western Saskatchewan.”

Rust spores can reach into the Peace region.

“It is a bit challenging this year, because with the moisture coming later, we’re getting towards the key time,” he said. “So, we might have some late development, not only in the leaf spot, but if you look at sclerotia and sclerotinia, they need about three weeks of soil moisture close to field capacity.”

If it’s been dry and then rains soak the field to capacity, spores could be released in about three weeks, he said.

“What it might mean, in this year, is that the main crop of spores will come into that canola crop as it is moving into full bloom or even later crop growth stages,” he said.

However, decisions on whether to spray can be challenging.

Turkington recommended looking at the weather forecast over the coming two weeks. If one week is dry and the next is wet, it could have an impact.

“If you could tell what your next two to three weeks would be like as far as weather, that could tell you if you could spray now and you could provide some protection during the next two to three weeks, when there might be some infection that could not cause huge yield losses, but in that five to 10 per cent range, plus reductions in kernel weight and bushel weight,” he said.

Wheat and barley cereal heads can be infected with fusarium head blight or fusarium graminearum in the boot to late milk/early dough stage to senescence, he said.

The kernels can look healthy, but there can be superficial infection and production of deoxynivalenol (DON).

“I would have a close look at the crop and what’s happening in the crop,” he said.

Sclerotinia and fusarium head blight are diseases where producers have to make the decision to spray before they see symptoms.

“You have to rely on weather maps and other tools that might assess inoculum levels, in the case of sclerotinia, whether it is a spornado, spore map or petal testing,” said Turkington. “In contrast, with your leaf spot diseases, you can follow a disease in the crop and use that as a guide in terms of risk.”

He recommends looking for disease while scouting for weeds. Disease serves as an indicator that the crop needs to be monitored more closely. If there is no leaf spot disease in the upper and middle canopy, spraying may not be useful, he said.

But if disease is developing in the lower canopy and moving up, and if there is cooler weather with more rain, disease may cycle in the crop.

“It may be worthwhile to spray a fungicide to provide some protection to that upper canopy tissue,” he said.

Most products give a two-week window of protection, which can keep the disease under control while the crop grows.

“If you aren’t seeing symptoms in your crop and you continue to see no symptoms, our experience in what we see in commercial fields is that it’s likely not going to pay to spray a fungicide,” said Turkington.

This doesn’t apply to fusarium head blight. Growers need to look at risk maps, previous history with the disease and the pathogen in the presence of harvested grain, he said. If the history is there, it may be beneficial to spray.

Turkington has also seen bacterial leaf disease lately, more commonly over the past two to three years in southern Alberta. The disease pops up in fields that have seen significant thunderstorms. It causes long greasy stripes on the leaf. There is no cure, other than being cautious about seed sources, and extending rotations, he said.