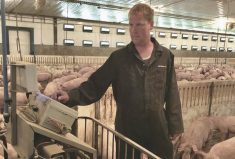

When Chris Fasoli exited his office job in 2015, he knew he wanted to do something different.

After some soul-searching, he and wife Jessica decided they wanted to farm. The Fasoli family operation, run by Chris’s brother, had some grazing land available after selling off its cattle a couple of years earlier.

But the couple faced a dilemma.

“Getting into farming is extremely expensive and farms are very generational,” said Jessica.

Restarting a cattle herd was too expensive, so the couple decided to give pigs a try, starting with just 70 animals with a mix of Duroc and Landrace genetics (developed by a breeder with more than 30 years of experience). But building a hog barn was also too costly, so their pigs would be raised outdoors year round and bedded on straw (and not given antibiotics or feed with GMO ingredients).

Raising heritage pigs this way has become a well-travelled route in recent years and like many such other operations, the Bear and the Flower Farm has been a hit with foodies.

But the operation, located near Irricana, has done something very different — it is the first outdoor hog farm in the country to achieve Canadian Quality Assurance (CQA) certification.

“We’ve advocated for outdoor farms to have borders and to have biosecurity,” said Jessica.

When they first approached Alberta Pork, they were told it simply wasn’t possible. The certification program is designed around Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) principles and officials didn’t see how the couple could control risk factors when pigs are in open-air pens with straw and dirt, and potentially coming into contact with mice, birds, and deer that could introduce disease.

Read Also

Pigs turn the thermostat down

A study from the Prairie Swine Centre showed that pigs prefer to keep temperatures lower in the barn when they have control of the thermostat, which helps producers keep their pigs happier and save on their utilities bill.

Moreover, the Bear and the Flower Farm had been growing by leaps and bounds. It now has a herd of 1,600 animals and slaughters 60 to 80 pigs weekly (roughly the size of their original herd).

But that growth was actually a big driver in seeking Canadian Quality Assurance certification — the couple had long moved past the days of slaughtering pigs themselves and needed that certification to be able to send animals to a federal slaughter plant.

So the Fasolis persisted, working with Alberta Pork, the Canadian Pork Council, and their veterinarian to create, and implement, a long list of protocols that would allow their farm to be certified.

“When we first got into it, we didn’t know that you had to fill out swine manifests,” said Jessica. “We didn’t know you should wash your trailer after you leave the slaughter plant. We didn’t know about deworming and all of these things. It was a learning curve.”

Like operations raising pigs in barns, the Bear and the Flower Farm has tight biosecurity rules, including defined boundaries that the pigs must stay within and visitors cannot cross. Convincing officials from pork organizations and the federal government (CQA is recognized by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency) was a major effort — which included creating a long list of standard operating procedures, having farm audits, and providing lots of documentation.

But it was worth it, said Jessica Fasoli.

“We passed the pilot in March (2018) and now we can export anywhere in the world,” she said. “That’s pretty much amazing for an outdoor farmer. We didn’t have the same rights as barn pigs.”

The couple has been equally busy on the production front.

“There’s a complete science to how you raise pigs and we were 100 per cent blown away by how nerdy pig raising gets,” said Jessica.

The couple has built little huts for their pigs to use when it’s cold and a “splash park” for hot days. (Pigs actually handle cold weather better than heat.) Working with a swine nutritionist, they’ve also developed a pelletized feed ration (with winter and summer versions to maximize feed efficiency), which includes prebiotics and probiotics.

“We started feeding our pigs flax as a way to help with their fat content and marbling and for their health,” said Jessica.

After their nutritionist suggested it, the Fasolis sent a sample of their meat for testing and found their pork contained three times the required amount of omega-3s.

“You can have 100 grams of our pork and get the daily requirement of omega-3s and omega-6s because we feed them flax.”

The couple has been equally busy on the marketing side of the business.

“I had to start out and literally pound the pavement and go into restaurants and ask restaurateurs to buy a whole pig. I had to learn how to be a different person,” said Jessica, who was a counsellor before farming full time.

Through feedback from chefs, the couple worked to perfect their pigs.

“At any given moment, we have five or six pigs tagged at birth and we are trying different things like getting our meat darker or more marbled,” she said. “We’re always doing beta testing. We want our pigs to be the best they can.”

Duroc pigs are a North American heritage breed, and the Fasolis grow them to capitalize on the animals’ loins and tomahawk chops (a long bone-in chop).

Their efforts are winning accolades, including at last month’s Cochon555 event at Banff, a major culinary event that drew nearly 800 people (who consumed 1,500 pounds of pork). The North America-wide competition pairs five heritage pigs, five wines, and five chefs in regional culinary events, with the winner of each competing for the North American title of the “Prince of Pork.” The Fasolis were partnered with Chef Scott Hergott, who runs the Banff Gondola Sky Bistro and is a customer of the farm.

It’s a long list of accomplishments for a couple who say they knew almost nothing about pigs four years ago. Commercial hog operations have been buffeted by a series of challenges (from devastating price plunges to disease issues) and the couple hopes their farm will be a model for others. (As of Jan. 1, other outdoor pig farms can apply for CQA certification.)

“The hog industry needs help,” she said. “Now we are massive advocates.”

But for customers of the Bear and the Flower Farm, there’s a bigger issue: Where did they get that name?

“It’s so cheesy,” said Jessica. “It’s our nicknames for each other. When I met Chris a long time ago, I thought that he looked like that skunk off Bambi whose name is Flower. Chris is Flower. I’m Bear.

“Every farmer names their farm after their last names. So we thought let’s do something whimsical, millennial and fun that people will remember. That’s where it came from.”