Dan Darling remembers the tough slog of negotiations in free-trade talks with Europe — and the hope that they would end with major gains for Canadian beef.

But five years after the signing of the Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement (CETA) with Europe, talks continue and potential benefits remain unrealized.

“When we were negotiating the deal, agriculture and beef were supposed to be — and could still be — the big winners,” said the Ontario cattle producer.

Read Also

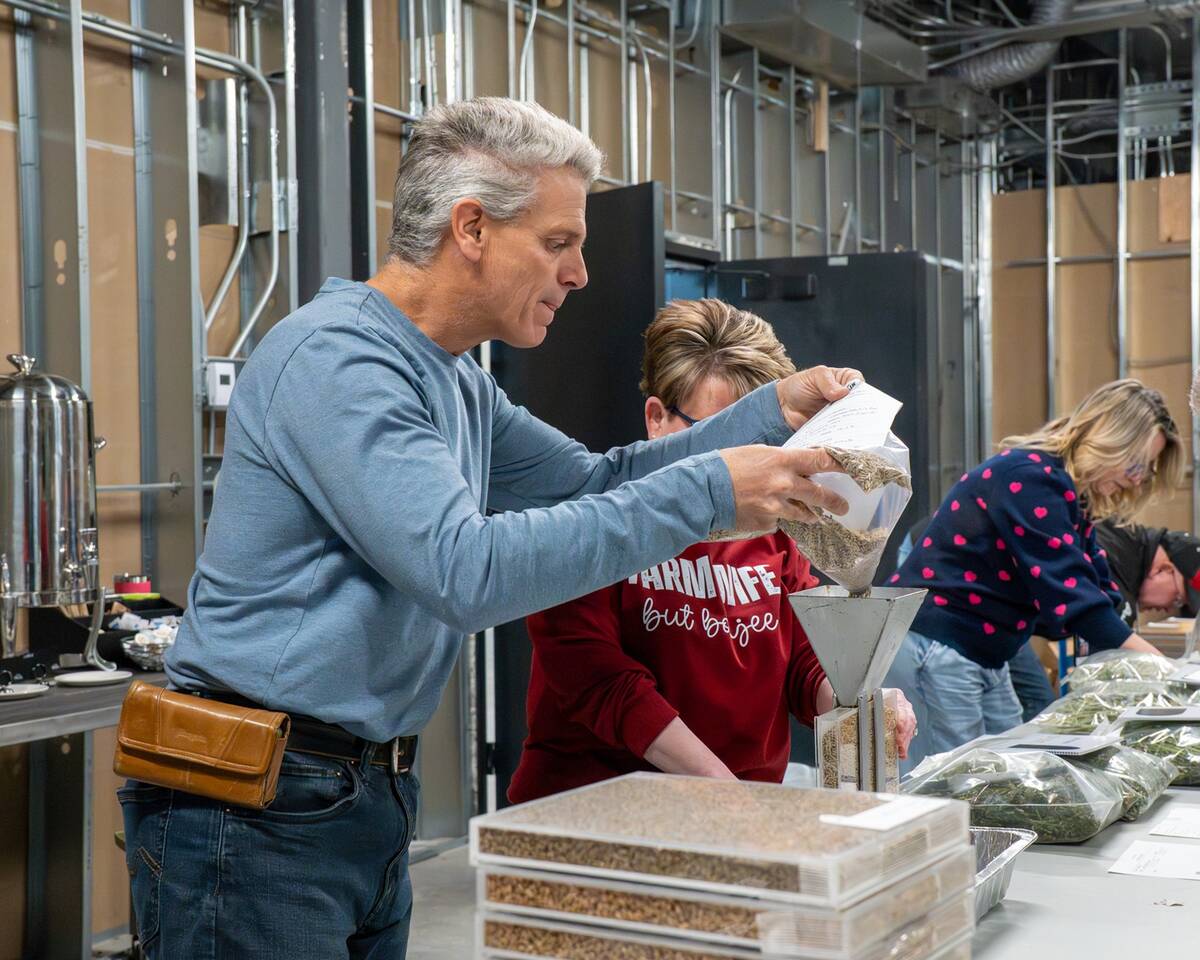

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

Darling was president of the Canadian Cattle Association when the deal was signed to great fanfare in 2016, after years of talks. CETA came into force in fall 2017. As CCA vice-president, Darling had travelled to Europe with two federal trade ministers (first Conservative Ed Fast and later Liberal Chrystia Freeland) as they sought to finalize the legal language and seal the deal.

“(The) understanding (was) that prior to signing the deal, there were still some little things that needed to be changed on the European side that would allow us to meet the goals that would make this a huge success for us, and for them, frankly,” he said.

[RELATED] CETA still not fully delivering

But those “little things” weren’t as easy to overcome as hoped.

“Our federal government and the negotiators are still working diligently to try to get these things changed, up until now, to no avail,” said Darling.

The first round of talks began in October 2009 and during the long years since, Bob Lowe has followed them closely, first as chair of Alberta Beef Producers and later as CCA vice-president and president (from 2018 to 2022).

“I wish it worked better,” said the Nanton-area rancher and feedlot operator. “I guess what it shows is that in a trade agreement, the act is one thing, but the carrying out of it is another thing.”

And the numbers tell that tale in dramatic fashion.

On paper, CETA allows Canada to export almost 65,000 tonnes of beef to Europe annually without paying tariffs. Back in 2017, the CCA estimated that would be about $600 million worth of business each year.

But the value of actual trade is barely a rounding error. Last year, just 1,450 tonnes of beef worth $23.7 million were sold to the EU, the cattle organization says.

“On the downside, there is a huge amount of product coming in from Europe because now we’ve opened the door and taken down any restrictions from their product coming in,” said Darling, who is now the CCA’s representative on (and president of) the Canadian Agri-Food Trade Alliance, a coalition of farm and food organizations pushing for fair ag trade rules.

“It’s a negative, not a positive.”

And the negative is getting worse. Last year, Europe exported 16,000 tonnes of beef worth $100 million to Canada. That means for every pound of Canadian beef sold to Europe, the EU sold 11 pounds here.

Currently, Europe is sending about 17 times more beef to Canada than vice versa, said Lowe.

“It’s a ratio of 17-to-one. We’re supposed to be one of the big winners in CETA and we’re one of the big losers,” he said.

“Our government has to be prepared to issue some sort of measure. The good thing about it is that it’s not a whole bunch of actual pounds, but it is a high dollar value that is flowing out of the country and not into the country.”

When it comes to trade deals, the rules — and how they’re implemented — need to be based on sound science, said Lowe.

That comes into play with the key factor keeping Canadian beef out of the EU. Major processors here use peroxyacetic acid as a ‘carcass wash’ to kill microbes before cutting. Europe doesn’t accept that, and switching to another method just for beef destined for Europe would be uneconomic.

“What we use is accepted all over the world as good or better than anything else, but because the EU doesn’t use it, they are basically using that as a non-tariff trade barrier,” said Lowe.

This issue has been discussed for years and Canadian trade officials were in Brussels earlier this fall seeking, once again, a way through the impasse.

“Hopefully they get it done. It’s a really high value market if we can crack it,” said Lowe.

Darling isn’t hopeful of a quick resolution.

“I would say there’s fewer negotiations — they’re basically at a stalemate,” he said.

“On the beef side, it would have to be something that they would have to change in their regulations and their government regulations in order for that to come in.

“From our understanding, these were things that they were going to change, but they’re not willing to.”

“We always assumed that science would win with the EU but it just hasn’t,” added Lowe. “We’re five years into it and nothing has changed.”

Another issue is the difficulty in getting EU certification for Canadian farms that wish to raise cattle for processors that do sell to Europe. That’s a result of a shortage of veterinarians who have been accredited by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to provide the required certification, said Lowe.

“If we had more EU approved farms, we’d be shipping more meat, but not nearly enough to correct that much of an imbalance.”

COVID-19 also slowed negotiations.

“It stopped anything of a personal nature, and you need that in these negotiations,” Lowe added. “It’s pretty easy to sit on a phone call or a Zoom meeting and say you’re going to do this, and not have to look the other guy in the eye.”

Yet another issue is that the trade deal has not been ratified by all EU countries, Darling said. All 28 member countries need to ratify the deal, and fewer than 20 have done so.

“It’s these other countries that are putting up the stop sign on any possible change,” he said.

Although Canadian negotiators are circumspect when giving updates, it’s not hard to guess how things are going, added Darling.

“You can see the frustration in their voices and their faces when they start talking about it,” he said, adding some of them have been at the negotiating table for five years.

“At this point, I think it’s safe to say that our biggest hope is that we’ve all learned a little bit from this negotiation as what not to do moving forward.”

Still, the Canadian ag sector has high hopes about the upcoming trade deal with the United Kingdom, said Darling.

While EU trade deal is often cited as a template for the one to be negotiated with the UK, it will have to be much different when it comes to meat exports and imports, said Lowe.

“We’ve already told the UK that if any free trade agreement is just a replica of CETA, that we don’t want anything to do with it and we won’t support it,” he said.