Researchers at Olds College have found success removing excessive contaminants from feedlot storm ponds by using floating islands.

“If you’re not familiar with the islands at all, basically it’s an island constructed to grow plants on its surface,” said Dan Karran, principal investigator, ecohydrologist and instructor in the Werklund School of Agriculture Technology at Olds College. He emphasized the data in this project is preliminary.

Karran and his team wanted to find out whether native wetland plants grown on the islands could clean water in cattle feedlot ponds. Floating islands, which are four feet by eight feet, are started on peat moss, but the root system develops into the water body.

Read Also

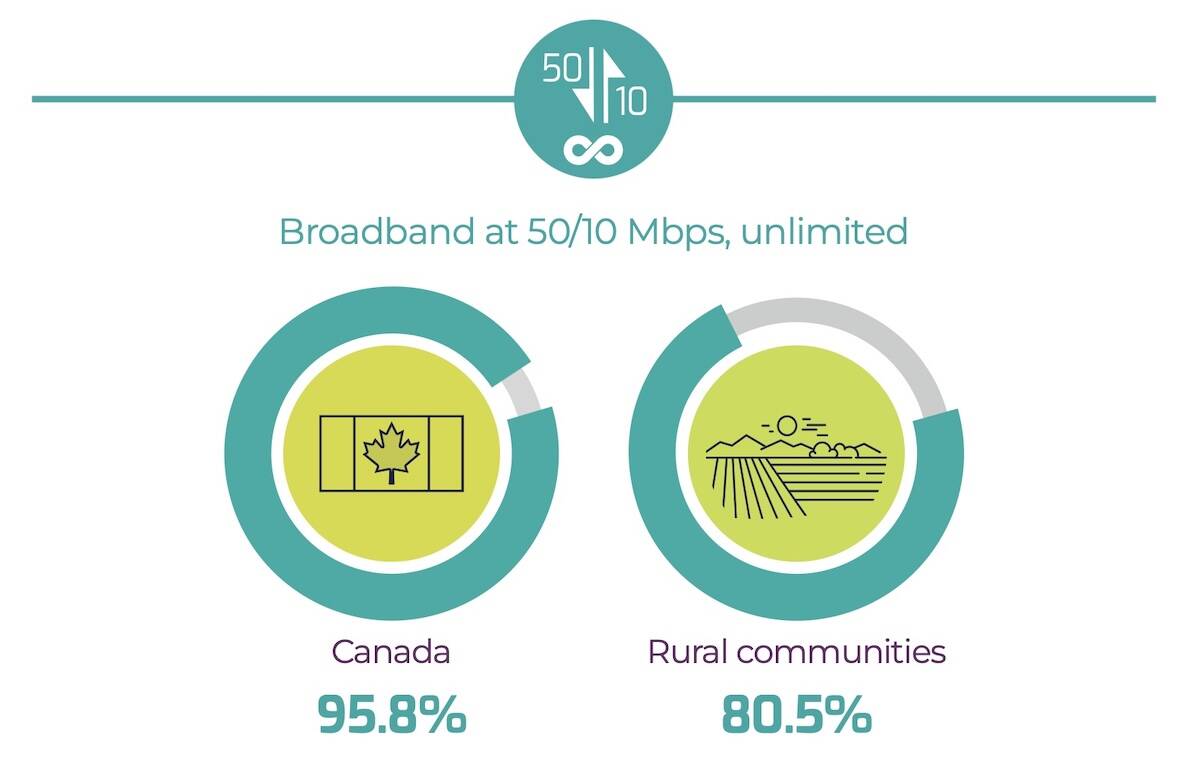

Rural Alberta gets further boost to internet connectivity

The province and feds join forces to help remote/rural Albertans get connected to reliable high-speed internet through its Broadband Strategy.

“In a lot of ways, it’s kind of like hydroponics,” said Karran.

The plant roots take up nutrients and other contaminants from the water. Floating islands are patented technology created by Tannas Conservation Services, who were working with Olds College on other projects. The islands are an environmentally-friendly, natural technology powered by sunlight.

Storm ponds in a cattle feedlot are water that runs off the feedlot during a storm.

“It’s a holding pond for all that water, because, as you can imagine, if you have a storm on an area where there’s 12,000 cattle, you’ve got a lot of contaminants entering that runoff,” said Karran.

The federal government has passed legislation that these ponds cannot spill into natural waterways, said Karran.

“They have to be contained, and they can’t leak into groundwater, because they’re very high in contaminants, nutrients, e.coli, harmful bacteria and a whole host of other things,” he said.

“They’re probably the most extreme environment you can test these islands out in because they are so contaminated with such a variety of different contaminants,” he said.

The researchers tested the floating islands at two feedlots near Linden in central Alberta. They also had a control pond without any islands at Olds College. The project involved 55 islands in total: 41 at one site and 14 at another smaller site.

The goal was to use native cold climate wetland species normally found in in northern and southern Alberta. The islands were installed and monitored for two seasons. Six plants were planted on the islands, but only three survived. Each of the surviving plants performed differently.

“We found that Baltic Rush performed the best, Water Sedge the second best and Wheat Sedge the third best,” said Karran.

The plants were able to remove a sizeable number of contaminants from the water. Researchers found the plants removed 69 per cent more ammonia, 55 per cent more total phosphorus and 27 per cent more total nitrogen compared to the Olds College control feedlot ponds. The islands also removed 93 per cent more copper, 81 per cent more aluminum and 77 per cent more zinc, compared to the Olds College control pond.

High concentrations of phosphorus and nitrogen in water can pose problems and lead to algae blooms.

“If you have too many algae in the water, it suffocates all the other aquatic plants and animals,” he said.

Blue green algae can produce a toxin which can kill or injure animals.

“Cleaning dirty water is important so that you can reuse the water, or you can put it back into its natural environment. In Alberta, especially right now, we’re dealing with potentially scary drought conditions,” said Karran.

“Water is a lot more variable these days because of pressures like climate change and that sort of thing.”

Karran said there is a lot more competition for water resources.

“When you’ve got these large volumes of dirty water sitting on some of these ag operations, if there’s a way to clean that water so that you can reuse it, and clean it in an economical way, so then it’s available for reuse around your operation, that’s an economic benefit to the operator,” he said.

The research project began in 2020. The next step is to look at the rate of return of investment.

“How much can you expect to get out of these islands for the cost? Is it worth it, for larger scale environments or the small environment?” said Karran.

The final report from the project should be available in September 2025.

Karran said the use of floating islands may be transferable to other bodies of water, such as farm dugouts and water ponds on golf courses.