The layoffs have already started in Alberta’s energy sector — but many more are on the way, say experts.

“We’re estimating somewhere in the range of $12 billion less investment taking place,” said Michael Burt, director of industrial economic trends with the Conference Board of Canada.

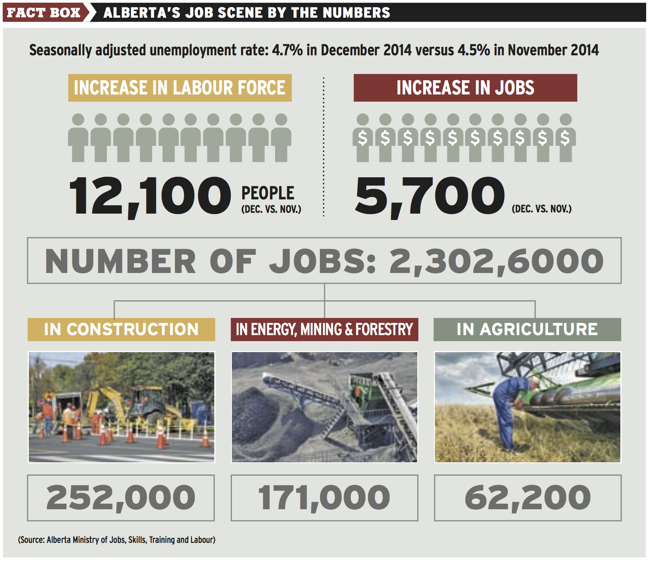

“That’s going to translate into thousands of fewer jobs in the oilpatch and also in the construction industry associated with developing oilsands pipelines.”

“We are expecting some job losses in the energy sector and I think that translates into some nice, juicy resumés coming through the door of forest and ag producers,” added Todd Hirsch, senior economist with ATB Financial.

“That’s a benefit — and people will not have to back up the money truck to get them.”

Farm employers across the country have struggled to find workers, and the fact that there are “close to 50,000” temporary foreign workers working in Canadian agriculture is evidence of that, said Burt.

But the big problem in Alberta has been competition for workers, such as truck drivers, that are in demand in both agriculture and the energy sector, he said.

“They may find it easier to get a job in oil and gas, or they may get higher pay,” said Burt. “So you’ve seen people in particular occupations being drawn out of agriculture, and likely other sectors as well, into oil and gas when the boom was occurring the last few years.”

Agriculture has also had trouble attracting unskilled labourers who have been drawn by the high pay and high demand for workers in the energy business.

But that was then — the landscape is dramatically different now, said Burt.

“Basically, those people who were working in the oilsands or the oil and gas sector will be looking for jobs elsewhere. Agriculture and other sectors will likely benefit from that.”

Read Also

Alberta producers share why on-farm research drives success at RDAR showcase

Farmers explain how producer-led trials and strategic data collection are bridging the gap between the lab and the field in their operations.

Attracting workers

So how can producers grab hold of some of these workers?

Use some of the same tricks that oil and gas companies do, suggests Cheryl Knight, an oil and gas human resources consultant based in Calgary.

Knight promotes a “multi-pronged approach” that embraces flexibility.

“The worker today is demanding much more flexibility,” said Knight, who spoke at the Agricultural Labour Summit in Red Deer late last year.

“We can complain about it. We can fight it. We can try to change it. But the best thing to do is to figure out ways to address it.”

The oil and gas industry has been built on a “mobile workforce” — skilled workers from other provinces who are offered customized work rotations, said Knight. And producers can attract farm workers using a similar system.

“You can target areas of high unemployment across Canada where there are skilled people who are unemployed,” she said.

“What opportunities do you have to address some of your labour supply (problems) through mobile workers and rotations?”

Untapped labour pools

Producers should also be looking at “underrepresented supply pools,” as the oil and gas industry has done.

Youth are the easiest to attract — if employers make it easy for them.

“Youth do not know how to find you — they’re a little bit lazy in terms of how to find the sector and how to get into the sector,” said Knight, who suggests working with high schools and colleges to utilize or develop work-placement programs.

Immigrants are another labour supply pool that producers should consider.

“There are immigrants in Canada who are unemployed and underemployed,” said Knight. “They are the most motivated, skilled, educated, and flexible workforce that we have in Canada.”

And while Aboriginal workers can be difficult to attract, they also represent a largely untapped labour pool that producers should explore, she added.

“As we’ve found in oil and gas, partnerships with Aboriginal communities are critical,” she said. “It’s probably the most long-term prospect that we have, and it’s one of the prongs that we must work on.”

But producers also need to be willing and able to invest in training and development if they hope to attract and retain farm workers, regardless of whether these workers came from the oilpatch.

“You’re going to have to train those people who have transferrable skills, but not 100 per cent of the skills that you need,” said Knight.

“There’s no magic wand. There are low-hanging fruit… but you have to be working at things all the way through.”