The big shrink seems to be over — but Alberta’s cow herd is considerably changed from the pre-BSE era.

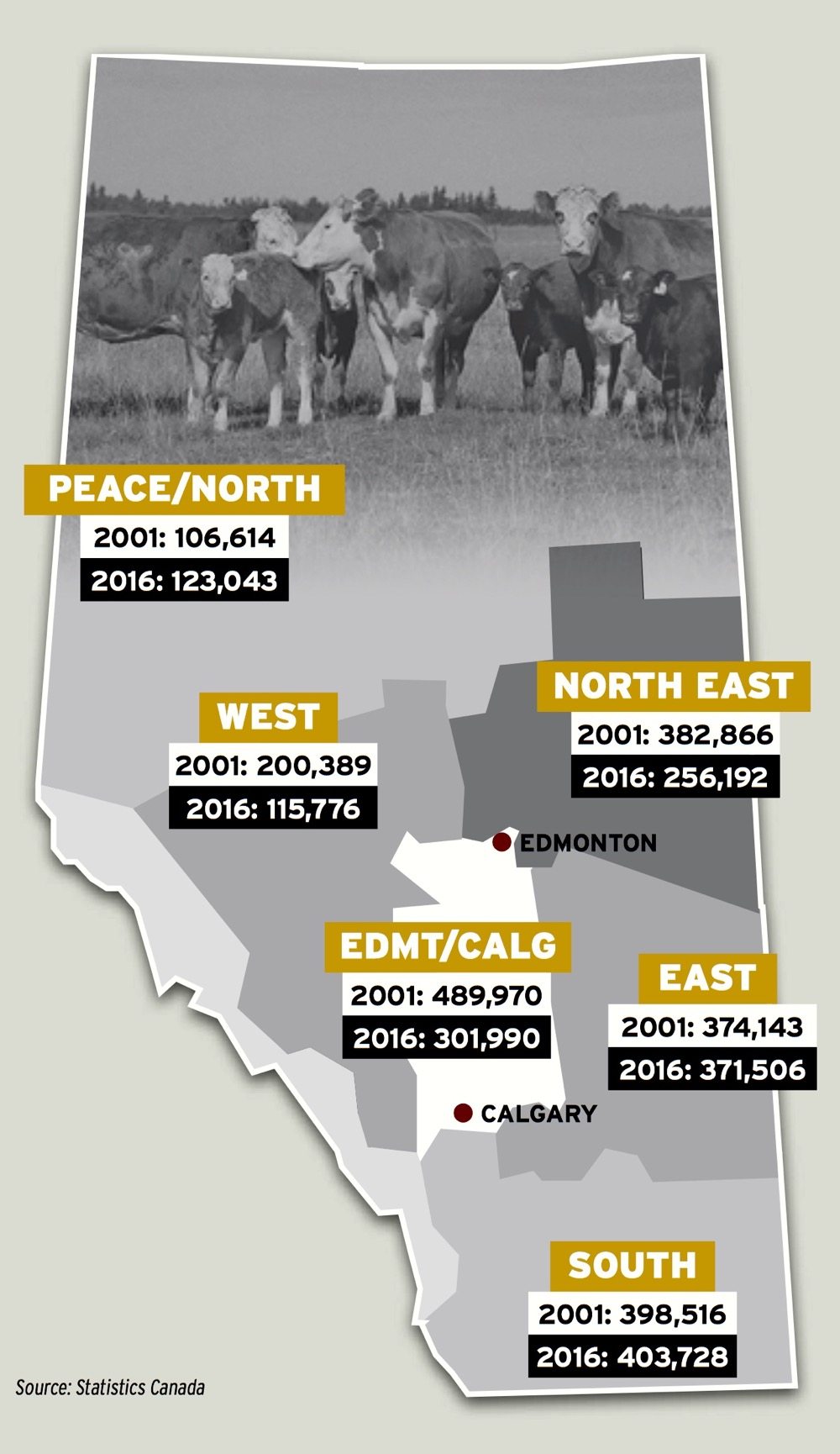

The latest Census of Agriculture found 1.57 million head in the province in 2016, a very slight increase (of 13,500 animals) compared to five years earlier. The herd is not only much smaller than prior to the 2003 BSE crisis (when there were roughly two million head), but different in two key ways — location and the average herd size.

Three of the province’s six regions have lost a third or more of their cattle since 2001 while the two biggest cattle regions (southern Alberta and east of the Highway 2 corridor) are around where they were in 2001.

Meanwhile, the average herd has got considerably bigger — to 95 cows per farm in 2016 versus 63 cows in 2001.

So what will the next decade or two bring?

Here are some thoughts from four Alberta producers.

Charlie Christie

400-head cow-calf operation along with a feedlot and grain farm near Trochu

“To be a full-time rancher, economics of scale will play a part — we’ve doubled our herd in the last five to 10 years,” said Christie, who is also chair of Alberta Beef Producers.

But that still leaves lots of room for small operations, he added.

“You’re always going to have these smaller herds that guys keep around because they have a love of the industry and some grass.”

Other factors could be more important in determining what happens to Alberta’s herd, he said. Overregulation is a big deterrent, market share (abroad and at home) is critical, and “we have to prove once again that we’re producing a super food,” he said.

Efficiency and environmental stewardship will also be key, but what’s exciting is a new sense that the two aren’t at odds with each other but actually go hand in hand, said Christie.

“Something we’re beginning to realize and our public is beginning to realize is that every time we improve things as a producer and grow things for less dollars, that accounts for a smaller carbon footprint and smaller load on the environment, with less water use,” he said. “The adoption of new technologies and the adoption of new research, the willingness to invest — that’s what I see as a huge part of our industry.”

Lyndon Mansell

Cow-calf operation and grain farm near Innisfree

While the trend has been to larger herds, that may not necessarily continue, said Mansell.

“With mapping the genome and genomics, I’m thinking that a smaller herd could put the genetics together to achieve a certain purpose and a certain carcass weight. There’s opportunity there,” he said.

Labour shortages are also a factor that big operations will have to contend with. Canadian agriculture is currently short more than 60,000 workers and some think that figure could double in the next five to 10 years, he said.

“A lot of operations are now pretty much forced to use temporary foreign workers or they need to find something to do to keep employees busy year round,” said Mansell.

And big ranches are essentially out of reach for new entrants, he added, saying young people starting out need about $1 million for a 500-cow operation. That currently means you need family to get you started, but a different path — at least on the land side of things — might open up in the years ahead, he said.

“I think landownership is going to drift on to something else,” said Mansell. “Producers are going to own less and less of what they farm. I think a lot of the native range is going to be used and grass management will play a bigger role.”

Dave Solverson

Feedlot operator near Camrose

It’s hard to say how large herds might get in the coming years, but big is certainly the way many families have gone, said Solverson, a past president of the Canadian Cattlemen’s Association.

“If it’s a multi-generational farm, you need 300 to 400 cows to have a decent level of income,” he said.

But more cattle means more land and given the price of land in many areas, including his, it’s a tough equation to make work, he said. Still, in his view, there’s no way the herd can shrink without jeopardizing the prospects of the two big beef-processing plants in the province.

“It’s critical to maintain our numbers to keep the cattle in Western Canada,” said Solverson. “We have to keep working on the demand.”

The key to maintaining herd numbers will be using technology to improve efficiency and profitability, he said.

Melanie Wowk

Commercial cow-calf operation near Beauvallon

There’s no way to know how big herd sizes will need to be since most people currently rely on mixed operations to make a living, said Wowk, who is also a veterinarian and finance chair of Alberta Beef Producers.

But the key to a robust cattle industry is having strong export markets, and a big part of that is to protect against diseases such as foot-and-mouth or BSE, she said.

The ability to keep a lid on input costs will determine how the industry fares, she said.

“As cow-calf producers, that’s where we are. We are kind of at the low rung of the ladder. When there are input increases, it really affects our making money at the end of the day.”

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

It is important to talk with consumers, and correct the misunderstandings about hormone free and antibiotic free, she added.

Finally, it will be important to keep youth engaged in the beef side of agriculture and get more students involved in large-animal practice and research.

“We have to make it affordable and we have to make it a career choice they can make a living at,” said Wowk. “We’re losing a lot of researchers in Ag Canada over the next few years. Some of them from retirement and some from funding.”