An ‘atmospheric river’ on the West Coast caused unprecedented damage and shut down Alberta’s vital link to the sea. So, we thought it important to ask, ‘what is this weather phenomenon and will it happen again?’

A new term: Atmospheric River

Read Also

How Earth evens out the energy input

Earth has surpluses of radiation in its equatorial regions, and deficits toward its poles. Our weather is a matter of Earth trying to even out the imbalance, Daniel Bezte writes.

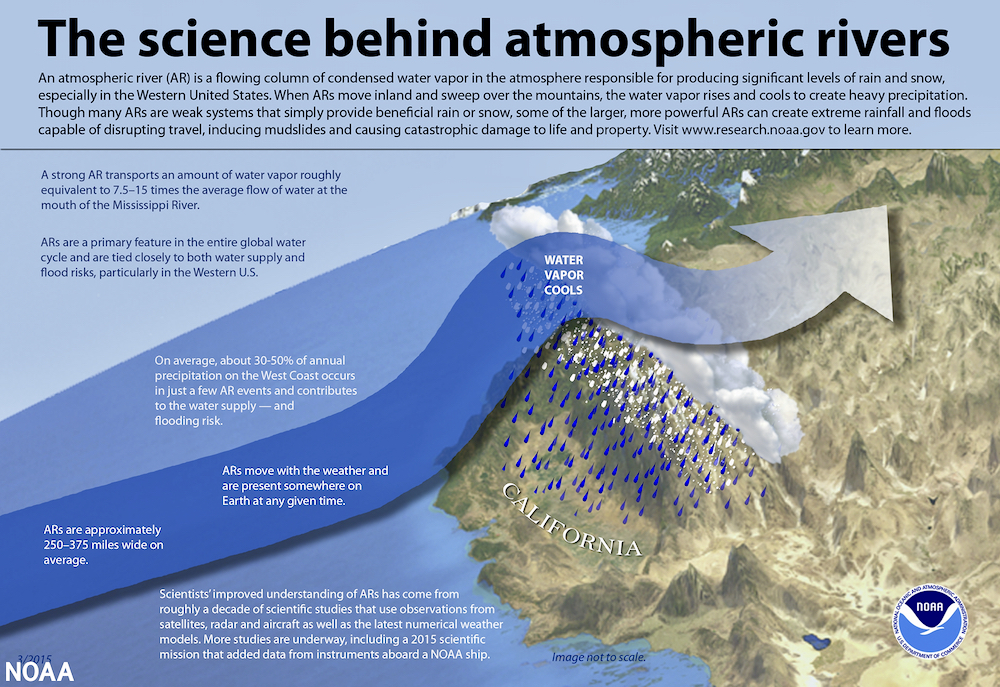

The unprecedented and catastrophic flooding in B.C. brought yet another climate term into the public view. And while ‘Atmospheric River’ may not sound as threatening as ‘weather bomb’ or ‘polar vortex,’ this moisture-laden stream of air dumped 200 millimetres of rain (or even more) over a huge area in little more than a 24-hour span.

What is an Atmospheric River?

At its simplest, it’s a water redistribution system: A current of air containing an extremely large amount of condensed water vapour. It is relatively narrow (although still a few hundred kilometres wide) and a strong one can contain as much as 15 times the amount of water flowing out of the mouth of the Mississippi River. That’s why it can dump a foot of water on an area in a day.

How often do these Atmospheric Rivers occur?

Continuously. There’s always several somewhere on the globe and they’re a regular feature along the western coast of North America. As one moves inland over hills and mountains, the air mass cools and as result, it starts shedding moisture. It’s estimated they account for a quarter (or more) of the rainfall along B.C.’s coast. You’ve even heard of one particular type before: The Pineapple Express.

Why was this one so bad? And will there be more like this?

The one that hit B.C. was a Pineapple Express, which means it originated in Hawaii and contained a lot of warm air — and the warmer the air, the more moisture it holds. But no one can say for sure why this one was so bad (although there were contributing factors, such as the rain also falling on early-season snow, which then melted and increased the surge of water down mountain sides). Climate models predict that as the atmosphere warms, these ‘rivers in the sky’ will be slightly less frequent but more intense. If that’s correct, there will be extreme rainfalls more often.

What does all this mean for farmers?

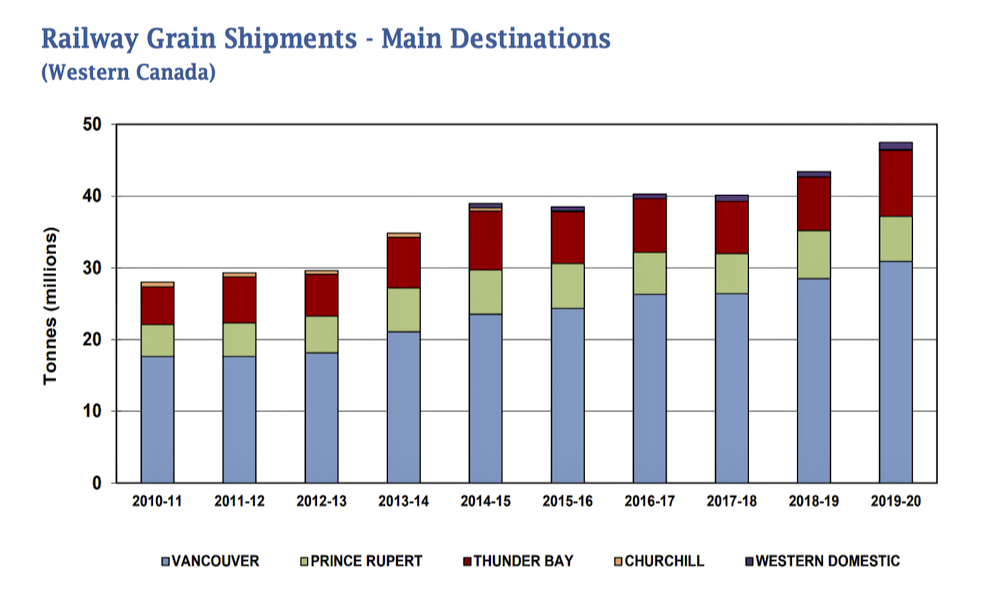

Simply put, they can’t afford to be cut off from the Port of Vancouver. The port already handles more than two-thirds of western Canadian grain exports and that share is steadily climbing as sales to Asian-Pacific markets increase. Virtually all of Alberta’s grain and most of Saskatchewan’s go through West Coast ports (with Vancouver taking four to five times more than Prince Rupert). Vancouver also handles a fair amount of fertilizer coming into Canada (67,000 tonnes in 2020). In short, the port’s slogan — ‘Connecting Canada to the world’ — is doubly true for western Canadian grain farmers.