Farms hold promise for generating biofuel and clean biogas to power us into the future, and they also have the land base for building energy systems.

But there is a vast difference between the capture of methane on site to produce gas and the permanent use of food production land for solar panels or wind turbines.

The goal of a green future may be misguided when there is risk of jeopardizing well-being by taking productive land out of the food system.

Read Also

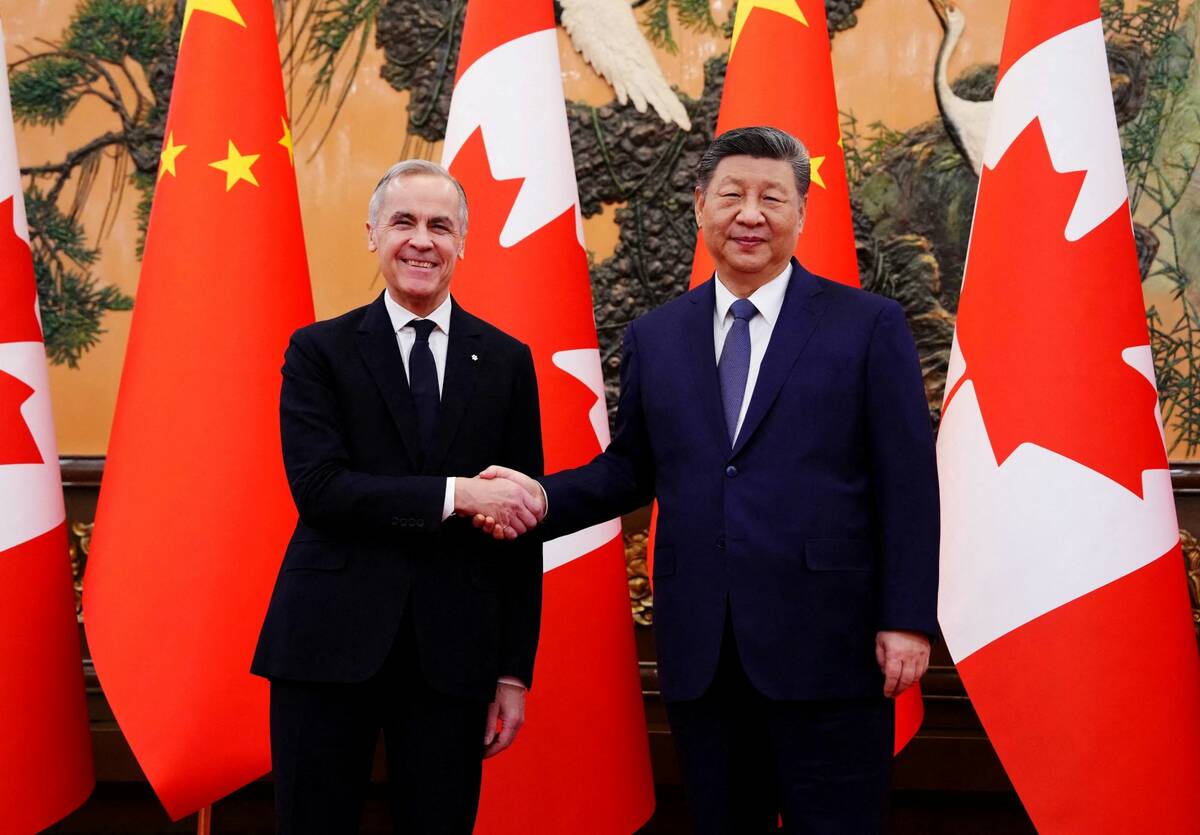

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

Coal and fossil fuel have been the dominant sources of electricity in much of the Prairies, and increasing solar power is an admirable goal, but not at the expense of good farm land. Most of the proposed 35 solar farms in Alberta are still seeking approval or in early stages of construction, but the province is already home to the nation’s largest solar farm near Vulcan, which covers nearly 3,300 acres.

More with Brenda Schoepp: Misconceptions about manure fly in face of common sense

There is no question that after the panels are manufactured, they are relatively non-emitting until they are trashed. However, while solar panels were originally expected to have a 30-year life span, many studies now indicate it’s closer to 15 years, as the rapid improvement in technology has increased the capacity of solar panels by 70 per cent since 2011.

But that leaves us to wonder about the future of the current panels.

According to the Harvard Business Review, solar panel waste will be 78 million tonnes by 2050. Some new estimates expect that to increase by 2.5 times.

Who pays for that? As the panel itself is largely glass, there are relatively few options for recycling, presenting a rural community environmental challenge.

Buying or leasing land for solar farms may seem good for the short term but when the technology changes, who is responsible for removal and land reclamation?

If the land is leased, this can be particularly important, as is controlling access and control of noxious weeds and other plants that will always attempt to grow in good soil. If the solution is chemical, then there is an environmental cost that might include runoff risks and leaching contamination.

Looking around the world, the result of solar panel farms can include desertification even on prime land.

Of great interest to me is the power produced. Most important is how the community will benefit from reduced energy costs.

There often is no commitment to reducing cost to the community where the solar farm resides. The power produced on the grain field, be that via panel or wind turbine, goes to an undisclosed location to an undisclosed buyer at an undisclosed price and may or may not be of any benefit to the people of the province. An increase in clean power has not led to cheaper electricity.

There is strong evidence that using abandoned parking lots, airstrips or other flat surfaces is a better fit.

In France, where 70 per cent of the power is now generated by nuclear, new laws will cover parking lots in solar panels in an effort to ‘not compete with land use.’ The nation recognizes that solar is a solution but farmland must be preserved.

With the amazing advances in technology, meeting green targets can — and should — be done without a footprint that compromises food production.

In Canada, less than four per cent of the land is arable, and it is disappearing fast. In Ontario, 319 acres is lost per day to development. In Alberta, the projected loss of productive farmland to non-agricultural use is 347,000 acres in the next 40 years.

Calculations vary, but it takes around 0.4 of an acre to meet all the caloric and dietary requirements of an adult year round. Taking that amount of land out of production for non-farm use equates to an empty plate for 850,000 Albertans.

If 15,000 acres of solar panels stand on food production land, then 37,500 folks do not have the future land base to support them.

It is not up to food banks to feed our families nor will we affordably offset our losses through increased food imports. The long-term opportunity is in adding value to locally grown food and food commodities.

Only this will ensure a robust and resilient community and keep the prime land doing what it was created to do — grow food.