The United Nations Climate Conference, COP28, recently held in Rome, was for the first time focused on agriculture. The outcome seems to be a set of seriously flawed directives for farmers.

In the 28-year history of the Conference of the Parties, agriculture has always taken a backseat. The 2023 meetings brought food production forward, not as the saving grace for global food insecurity, but as the culprit for climate change and the emitter of one-third of all greenhouse gases. And front and centre in the discussion were livestock and the accusation that their contribution to methane was paramount.

Experts claimed that livestock, that being farmed ruminants, were responsible for two-thirds of greenhouse gas emissions. Based on the narrow scope of one study, that spurred one of the three main directives of the conference, which was innovation in the livestock sector.

Read Also

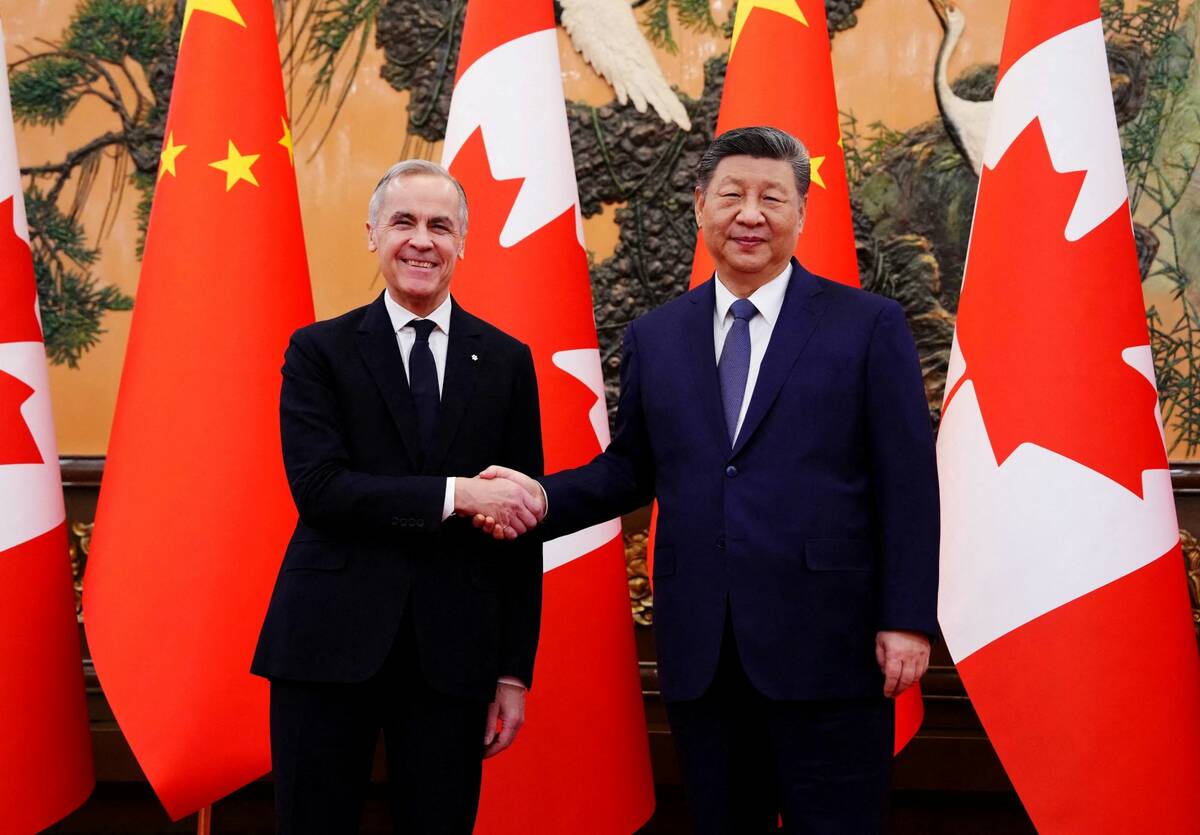

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

The 150 signatories, of which Canada was one, affirmed “that agriculture and food systems must urgently adapt and transform in order to respond to the imperatives of climate change.” Furthermore, the declaration said that “to achieve these aims – according to our own national circumstances – we commit to expediate the integration of agriculture and food systems into our climate action and simultaneously, to mainstream climate action across our policy agendas and actions related to agriculture and food systems.”

- MORE with Brenda Schoepp: From Beyond Meat to the return of meat

At first glance, it appears we are making progress with the promotion of cross-ministry policies. But Canada’s total output for all of agriculture is slight at 10 per cent of greenhouse gases and our nation’s response was not joint and did not come from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. It came prepackaged and ready to go from Environment and Climate Change Canada and was announced immediately following the COP28 meetings.

In the complex protocols for Canada’s program to incentivize beef producers to reduce methane emissions, it appears that to apply the protocols into practical action involves the assistance of a beef cattle scientist or researcher specializing in ruminants.

There is no indication at this time of the incentive or penalty within the context of the program, other than one line that claims there is an opportunity to generate offset credit.

It is not the project and related initiatives that are so concerning. Perhaps these will bring a long-needed boost to livestock research and attract more scientists, which is a positive outcome.

However, Canada agreed to expedite agriculture and food into climate action. Without in-depth consultation, that may have negative impact to an industry already suffering from high input costs and weather challenges. Neither Chief Climate Negotiator Michael Bonser nor Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault have served in any agricultural capacity in their careers.

Also concerning is the sudden emergence of methane expert groups. An example is the Expert Panel on Livestock Methane, a group of six academics who provide daily and very dire predictions. Their mandate is to reduce the emissions from livestock and reduce global livestock numbers.

One post recently read “1 million + premature deaths per year. Methane emissions from livestock contribute ground level ozone, a harmful gas that is responsible for one in five of all respiratory deaths.”

Shocking and also fraudulent. The sole source was an article in which mortality was estimated in males over 30 years old from poor air quality caused by nitrogen oxides, non-methane volatile organic compounds, methane and carbon dioxide in India, Pakistan, China, U.S. and Europe.

Ruminant producers, but especially beef producers, have been caught in a vortex of environmental emotion that is not supported by accurate science or informed advocates. Regardless of the conversation in some circles from those who may have never seen a cow, from either end, the reality is that when it comes to cattle, 53 per cent of the global population live in India, Brazil and China.

India, home to nearly 33 per cent of the world’s cattle, did not sign the declaration. And cattle are not the only ruminants on the planet.

There are 30 million wild deer, 68,000 giraffes, 1.4 million domestic sheep and goats (along with a multitude in the wild), 1.5 million moose, an unknown number of gazelles, 91 species of antelope in addition to yak and ox along with 204,000 buffalo and 15,000 head of bison.

And what of those with three-stomach compartments such as camels, of which there are 35 million domesticated and one million in the wild, and their relations such as alpacas and llamas? Are they contributing more than a monogastric such as a horse and, in doing so, are they also to be considered climate culprits?

Selecting the domesticated and most docile ruminant is certainly an efficient route when it comes to understanding the science behind rumination, but it is hardly representative of the mass of animals in the world with four compartments for food digestion.

There is a gap in understanding of the role of ruminants to use grass and other digestibles to produce milk, meat and much needed byproducts and to generate manure – one of the most valuable assets on earth, particularly in the face of soil depletion and dehydration and the need for alternative fuel sources.

For Canadian farmers with just 1.2 per cent of the global cattle population, the conversation itself is a challenge, as the industry and policy makers are short on accurate data.

For farmers and ranchers of all ruminants, the next few years will require additional research and strong advocacy to ensure they are not penalized nor put to pasture for producing food and valuable byproducts that do more to address climate change than ridding the earth of cattle in their natural environment.