The push to breed drought-resistant wheat has taken on new urgency as dry times become more common and more severe.

“Drought is big on everybody’s minds these days,” said Harpinder Randhawa, a wheat breeder with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Lethbridge research centre. “Especially in Western Canada, we rely heavily on the natural water availability of rainfall.”

Droughts are forecast to become more frequent in Western Canada, and climate modelling indicates more variability in weather patterns, said Ron DePauw, a retired federal wheat breeder who is now a science advisor for seed company SeCan in Calgary.

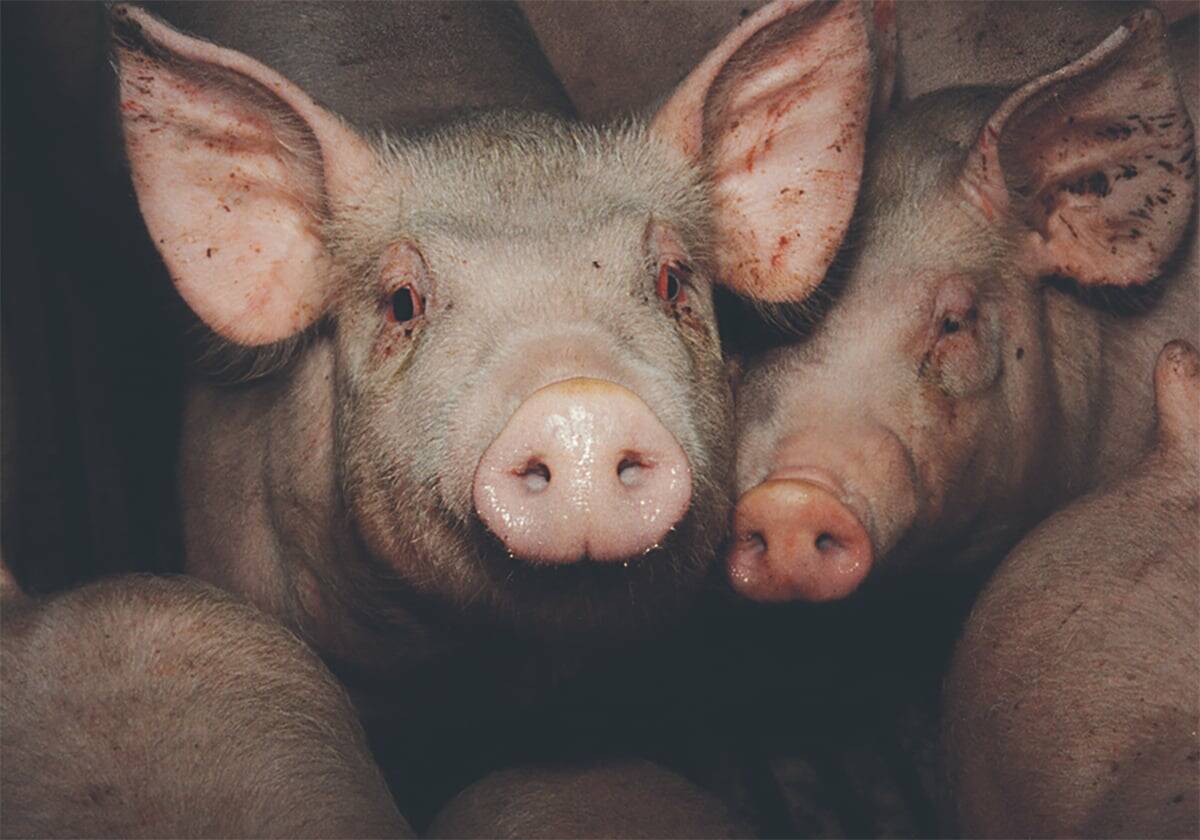

Read Also

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

After years of research, a University of Saskatchewan research team has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and how to control it.

“Summer temperatures will be warmer, with higher maximum temperatures,” said DePauw. “Moisture distribution is predicted to shift also. There will be less in July and August. Those are critical times for the growing of the wheat plant.”

The impact of climate change is already being seen, added Randhawa.

That’s backed by Alberta Climate Records, a website created by University of Lethbridge professor Stefan Kienzle that contains nearly seven decades of weather data, from 1951 to 2017, collected from hundreds of weather stations across the province.

The searchable database (at www.albertaclimaterecords.com) shows average mean temperatures in much of the province are two or more degrees warmer than in 1951 and many areas are seeing considerably less rainfall.

“Wheat doesn’t like either of these,” said Randhawa. “Wheat likes to grow in cooler temperatures.”

When it’s hotter, there are also higher rates of evapotranspiration.

“Drought is usually associated with a high temperature,” said DePauw. “When you have a high temperature drought, you can have high temperature and loss of moisture.”

[RELATED] Genomics takes wheat breeding into new era

The pivotal times

“If there is enough moisture to germinate, it will grow,” said Randhawa. “But the critical stage of the growing point is the tillering stage, about three to four weeks after germination.”

Tillering is directly tied to moisture availability.

“If (the plant) is hit hard at the tillering stage, you get just one or two tiny tillers, and that is a very big bottleneck,” he said. “You have just one or two tillers instead of five to six tillers, and that will have a significant impact on grain yield later on.”

Even if the plant gets past that stage, it’s not in the clear. Without enough moisture later on, there will be an abortion of the tillers, DePauw said. The same thing can happen to flowers if there’s intense heat or lack of moisture at the flowering stage.

“Instead of getting 100 kernels per head, you might only get 25,” he said.

Things can even go off the rails in the home stretch.

“Let’s say everything was good until the end of flowering,” said DePauw. If drought and severe moisture stress occur then, “the size of the kernels will be reduced.”

As many producers know from last year, all those things can occur in a single growing season.

“If the whole bloody season is drought shock, well, you’re going to have a scruffy little stalk, there’s not much for tillers, there’s only one head per plant, and only kernels of small size,” said DePauw. “That’s what happened in 2021.”

That’s called a terminal drought, said Randhawa.

“Wheat will just cook and dry very fast. You will have shrivelled grain. The in-fill period is shortened and the grain won’t fill properly. It has an impact on yield and quality.”

Not every field last year was hit at all those critical times, but conditions affected enough to reduce average prairie wheat yields to an average 34.8 bushels per acre in 2021.

The complicated quest

But it’s hard.

“Drought resistance is a very complex trait,” he said. “It’s not a simple trait that we can breed for, like rust resistance.”

Nor are semi-dwarf varieties likely to be the answer.

“Semi-dwarf varieties are less tolerant to drought because they don’t have a lot of root biomass — the shorter plant has shorter root biomass, too,” said Randhawa. “In drier conditions, you need a bigger root biomass, so they can go deeper and get moisture from the soil.”

The quest for drought resistance means breeders need to look at the entire plant, not just one specific trait. That package of traits includes factors such as root depth, plant height, how leaves operate (such as rolling up to reduce surface area and water transpiration), photosynthetic rates and water use.

It’s a complex mix of different factors that makes the mechanics of breeding more of a challenge.

Breeders screen for drought by growing wheat in fields in drought conditions, said Randhawa.

“You can do things in greenhouse or in controlled conditions, but it does not really give you a good picture if you want to develop a line because there’s a lot of interaction with other traits. You need field-scale screening.”

But there’s a major drawback to that approach. If there’s good moisture in a given year, trials won’t reveal much about drought resistance. The recent run of dry years has actually been a boon for breeders, Randhawa noted.

“The increasing frequency of drought over the past few years does provide a breeder with a tool to screen and select lines which are more drought tolerant, because if there is no drought out there, it will be very hard to screen and select for.”

Even then, the need to have lots of horses in the race complicates things. A breeder might start by screening 100 lines, select 10 that perform better under drought conditions, and then trial them to see how they perform.

Breeders are using germplasm from their breeding programs and from different wheat breeding centres, particularly international ones where breeding for drought and heat is also underway.

“We got some of the material and we planted that trial this year,” said Randhawa. “We will start screening in the next couple of years and will look for traits that perform best under drought conditions.”

The Lethbridge Research Centre and its sister station in Swift Current, Sask. — another semi-arid part of the Prairies — are prime locations. Testing promising varieties at both locations will aid the effort, said DePauw, who was senior wheat breeder at Swift Current before retiring. (He was dubbed the “billion-dollar man” in recognition of nearly 60 wheat cultivars he and his colleagues developed over his four-decade career.)

Though it can take 10 years to develop a new wheat variety, breeders do not have to start from scratch to screen for drought tolerance, said Randhawa.

“We have the material in the pipeline, coming in every year. We have lines that are going into pre-registration trials or registrations trials.”

Through use of genetic screening tools, breeders should be able to find drought-tolerant varieties in less time than it would take to breed new plants.

That said, there are no miracle varieties that will suddenly appear in the warehouse of the local seed dealer.

The initial focus is on finding varieties that beat the check by at least five per cent under drought conditions.

“You are looking for some type of genetic gain, and I think that would be at least a good start,” said Randhawa. “Then you build upon it, you generate more genetic material, and you build upon that.

“The key is to keep screening for drought and heat and maintain the yield as much as you have it, and always compare with the check variety to see how they perform.”