What could possibly go wrong? There is a farm, a will and the future.

Listening to the legal experts at a recent conference, it was a bit of a shocker to hear the situations in which farm families find themselves.

It is always best to have a will. This important document should eliminate confusion and lay a clear path forward during what is always a stressful time in the life of a farm family.

Read Also

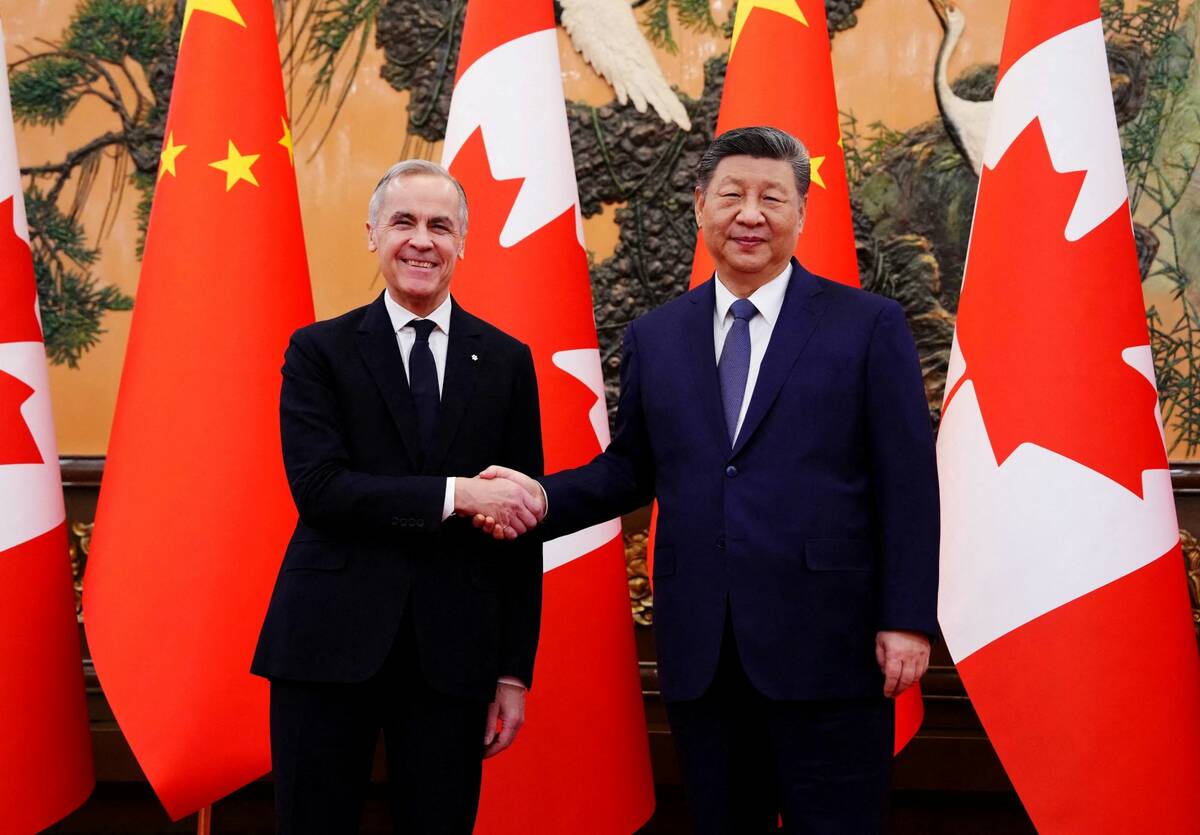

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

But often, in the spirit of fairness, the farm is left to all the children, regardless of farm size.

This leads to crisis as there may have been a participating child who lives on the farm and now must make a living on a slice of the land or engage the siblings in a collaborative and long-term rental agreement. In some regions, long-term leases are not encouraged, while other regions have a minimum farm severance size, so there could be a risk that the farming child won’t have the minimum required acres to farm.

In cases where there are several children and just one divided farm, the farm is almost always lost as the siblings fight it out over not only the land but the remaining assets. The only solution in most cases is to sell, regardless of what the farming child was promised. Depending on the agreements, lease payments and equipment investment may also be lost.

More with Brenda Schoepp: It was both an ordinary day and an extraordinary one, too

And selling is never easy because there can be differing views over the actual value of the property, especially if one sibling is trying to buy out the others.

When good intentions do not have appropriate guidance, the will becomes the instrument that precipitates the demise of the farm.

Because there is more than one asset, things become complicated. In addition to the land, there is machinery, livestock, tools, furnishings, savings, buildings, nuts and bolts, tools, crops, fruits and vegetables standing in the field and in the bin, cattle, lumber, metal, lubricants, machinery, autos, fuel, feed, inputs and contractual agreements to name but a few.

A farm under supply management also has quota and there may be outstanding contractual agreements. Or a project may only be half done and the question arises of who completes it and at what cost.

And it gets bad.

One person might want the crescent wrench while another the lawn mower and a third wishes to keep the small tools together. Sadly, I’ve been in garages where hundreds of tools are individually marked – and the whole process of closing an estate of significant worth is tied up because of the screwdriver set. While things are being sorted, the neighbour may want the air compressor or the bull back but there is no proof as to who owns the old beast. Even the neighbour’s assets may sit in limbo until ownership is determined.

This may seem petty, but it is as real as when siblings fight over thousands of cattle or four combines.

If the executor is one of the inheriting children, it can get pretty tense with big emotions and unintended outcomes.

New contractual agreements that may impact the ability to actually sell the farm to different owners are emerging. One untested area is the carbon credit market. These are long term covenants on land with payment to the owner.

If the terms are broken by land alteration or sale, what is the cost to the seller’s estate or the new buyers? In some contracts, the payment must be returned and in others, the carbon that was stored is negated. When the owner changes, are the new owners beholden to the carbon credit covenants in place? These are emerging questions in the field of farm law.

More important is the future issue of water.

Assuming that the farm is sold and no longer in the family, the water and water rights may be a non-issue. When there is enough land to split up, the focus is not only on the land fertility, road and utility access and buildings. Most stakeholders would be wise to want the parcel that contains a clean source of water.

Access to financing or the inability to access financing also contributes to inequity in the shared estate.

Not all persons can carry on and a critical piece of land, such as the one with the irrigation canal, may be sold outside the family. This leaves the remaining stakeholders with a lack of water and a potential handicap because of operational costs. It is something to think about.

The key in this discussion is to be absolutely clear on intent.

The parent must be clear and the legal representative has an obligation to ask for clarification and to write it in a way that reflects the intention and serves the best interest of the client and the family.

Where there is a will, there should be a way to ensure equitable treatment and to ensure that hardship or confusion do not dominate a very difficult time in the life of a farm family.